Organizational Transformation is the latest term for moving an organization to better results. Though the term may be new, the dynamics of making change happen remain unchanged.

Some years ago a Company (let’s call it “Ajax”) launched a Total Quality Management (TQM) initiative that was very successful. Ajax won national and international recognition for its quality performance. One day Ajax’s CEO confided to a visitor, “Our TQM program has been successful, but if I were to relax the pressure on people even a little bit, we would slide right back to where we were before.”

Sadly, this prediction came true. After this CEO’s retirement, his successor was bombarded with complaints about the complexity and bureaucracy of the TQM standards. The new CEO moved many of the standards to the back burner. In no time much of the pre-TQM culture reasserted itself. In a few years, Ajax was delivering inferior customer service compared to its key competitors.Ajax’s culture had been changed temporarily, but the business had not truly turned around.

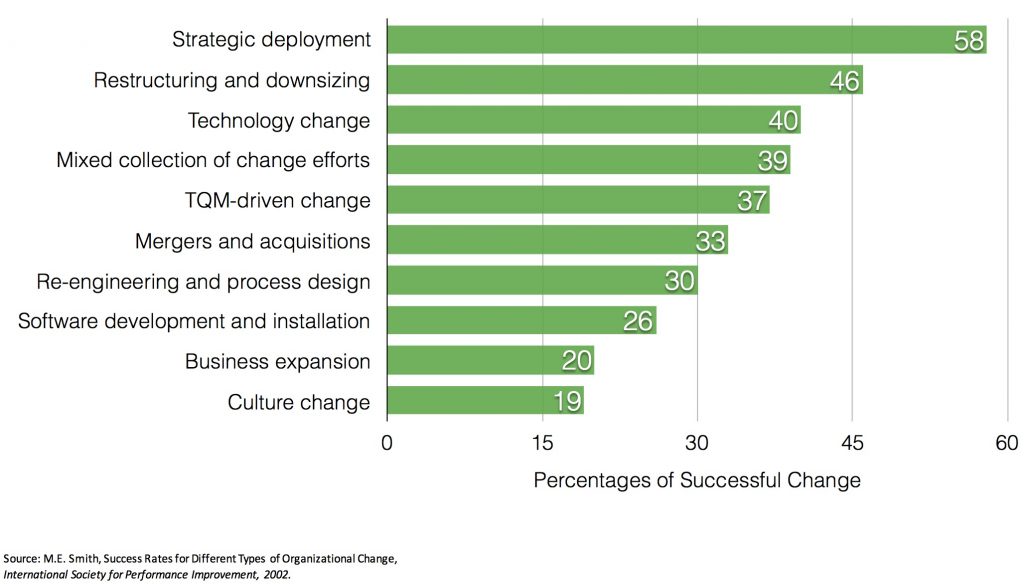

Ajax’s story is an all too common one. A study conducted by M.E. Smith summarized 49 published reports of success for organizational change, representing over 40,000 organizations. Here are the percentages of successful change reported for each change target:

How would you like to stake your future career on any of these percentages? And, these were just attempts to change one aspect of the organization’s operation. How many of these changes actually resulted in long-term business turnarounds?

Leaders Who Accomplish a Long-Term Business Turnaround

A business turnaround is more than the successful improvement in one specific area (i.e., Ajax’s focus on Quality). Turnarounds are accomplished and sustained by systemic changes in several key elements in the total organizational landscape. Examine any successful long-term business turnaround and you will find the leaders are doing many of these things:

1. Leaders have a holistic vision that adds value to critical stakeholders. Their vision isn’t self- centered or exploitive. It spells out a competitive advantage in the marketplace. It expresses deliverables that fulfill important needs of all key stakeholder groups.

A CEO once told me, “Our mission is to earn a profit. Period.”

I replied, “Good enough. Have that printed on a bronze plaque and hang it on the wall in reception areas in all your buildings so every employee, customer, supplier, and government official can see that you are only interested in your own profits.”

The global marketplace is teaching us that the cooperation and goodwill among very diverse stakeholder groups are essential elements in today’s business success. One example of such a vision is a “Strategy Tree” developed by US Synthetic (USS), a global leader in producing Polycrystalline Diamond Cutters (PDCs) for drilling into the earth’s surface. Two elements of their strategy tree are:

- Vision: to improve the lives of our employees, customers, shareholders, and communities

Core Values: growth, respect, trust, open, service, fun.These simple statements add value to every person and organization that does business with USS. From its humble beginnings as a family-owned business, USS has developed into the dominant global market leader for high end PDCs.

2. Leaders design new systems to deliver the vision’s better results consistently.

Even the most inspiring vision is only a statement of good intentions. It must be brought to life by the processes, systems, and work culture that all operate consistently every day. To truly lead a turnaround that lasts, the leader must be more than casually aware of the new systems and how they are playing out every day. Leaders at all levels need to be champions, not observers, of the new systems. I have seen how powerful this is when the leaders themselves actually participate in the design of these systems.

- One financial services organization made some systemic changes to take advantage of its strong client trust and its portfolio of financial services. The top 30 leaders in this firm designed systems that created synergies in how employees could cross-sell/recommend additional services to their clients. Against a history of single digit revenue growth in the past, the new systems delivered double digit growth in each of the following eight years.All stakeholders were enriched by this turnaround.

- The Krasny Manufacturing Company was caught in the middle of a major transformation when the Soviet Union dissolved and Russia now had to compete in a free market economy. Under the old rules, Krasny received production orders for its machine tools from one Soviet agency and shipment orders from another agency. Only a handful of managers had ever even talked to any of Krasny’s customers.

Now Krasny had to compete against western machine tools. Its managers had to obtain orders personally from customers. The Director General asked me, “What do we do in a free economy? Potential customers tell us they like our products, but they don’t have the money to purchase them?”

I told him, “In a free market economy you have to produce something that customers want and that they can afford.”

Krasny’s leadership went to work and created a vision statement. “We build our relationships as a team of people driven by common values in an atmosphere of trust and respect, based on the principles of integrity, fairness, equality, and mutual assistance.This is the only way that leads to the common goal.” This statement may not impress you, but for these leaders it represented a significant departure from their previous experiences.

Next came a series of brainstorming sessions inside every department. The objective of hundreds of discussions was to identify some new products that they had the skills to make quickly and that average Russian citizens could afford. Many ideas were suggested and a few were chosen for production. Krasny’s new product lineup included steel doors (theft had become a major problem in Russia because money no longer flowed to people automatically from the government; the steel doors prevented break ins). Other products were connectors for oil pipelines, a portable brick-making machine for the construction industry, and even children’s toys.

Talk about a turnaround! Krasny had to literally reinvent itself and how it operated to survive. New work processes had to be defined for the new products.The work was decentralized into self-sufficient units. Individuals were organized into work teams. And associates participated in a profit sharing plan. Krasny’s old factory buildings were converted into warehouses whose space was rented to western firms to store their products as they entered the Russian market.

Bottom line, at a time when two thirds of machine tool companies in Russia went out of business and hundreds of thousands of people lost their jobs, Krasny’s turnaround enabled it to survive.

3. Leaders recognize that organizational turnarounds are fueled from the inside out; new systems depend on individual turnarounds.

Organizations don’t have goals and deliver a turnaround; people have goals and deliver a turnaround. Turnaround leaders understand these dynamics and recognize that mandates, strategic documents, and goals alone don’t guarantee a turnaround. The people who must deliver the turnaround must feel ownership for its success. Spreading this sense of ownership from the leaders to all associates is an “inside-out” dynamic as illustrated by this “Genesis of Leadership” Model:

The core, or Genesis, of leadership is the leader’s sense of vision. But is this vision to be taken seriously by others? The leader’s commitment to and willingness to sacrifice for this vision inspire others to do the same. When a leader, team, or organization “walk the talk” of a worthwhile vision, trust relationships are created.Add to this scenario some leadership competencies such as inspiring communication, people skills, and structuring work to enable efficiency, collaboration, and support and the potential for a culture turnaround is increased greatly.

• I once worked with a company that was having serious financial difficulties. The parent company was not pleased with the situation and the whole organization was under duress. The CEO invested in a leadership workshop that not only taught leaders how to turn around their business, but also certified these leaders to teach the workshop to their associates.

In the hallways during break time, the CEO overheard comments to the effect that “these are great concepts and ideas, but it’s not the real world.”

The next day the CEO had something to say to the group. “I have heard what some of you are saying – that what we have been learning here is not like the real world. I need to make it very clear to each of you: In this organization this is the real world. Others may manage from the top down. Others may try to win at others’ expense. Others may say ‘do as I say, not as I do.’ But in this organization these things we have been learning are the real world. I’m staking my career on it!” You could feel the attitudes in the room shift significantly.

After the workshop, everyone returned to work. Workshops were delivered by their leaders to all associates. Processes changed. Systems changed.The culture changed.And the business turned around: double digit growth in profitability (compounded annually) the next few years and continued strong performance thereafter.

4. Leaders make it their business to see that the required systemic changes are actually doing what they are supposed to be doing.

Formal reviews and updates are helpful (as with any other important business priority), but turnaround leaders also check in with associates in different ways to monitor progress. For example:

- Some leaders have informal group discussions with associates to get their feedback on the new systems. When certain themes emerge from such discussions, it informs the leaders as to which issues are systemic and which may be specific to a particular leader or group.

- One vice president, who was skeptical of newly- structured cross functional business teams to manage each major brand, commissioned a formal survey of every person who was on one of the teams.After the 150 surveys were completed and the results were in, this vice president was surprised to learn that over 85 percent of these senior managers felt these teams were very worthwhile and were delivering solid advantages in the marketplace. After 18 months of operating with these teams, the organization had tripled its profits. And the growth has continued ever since.This turnaround silenced all the skeptics.

- One company included specific questions in its annual employee opinion survey that asked for feedback on different elements of the vision and organization design. This feedback helped leaders identify any trend problems and organize approaches to counter them.

5. Leaders recognize that even true turnarounds need to be renewed as market requirements evolve over time.

Even the most successful turnarounds run the risk of becoming out of sync with the evolving market requirements.This reminds me of a line in the award-winning film Why Man Creates by Saul Bass:

“Have you ever thought that radical ideas threaten institutions, which in turn become institutions that resist radical ideas that threaten institutions?”

Translation: Those who sacrifice to shape a turnaround may themselves become enemies to future needs for change.

How do leaders escape the trap of being so enamored with their own turnaround efforts that they become blind to the continuous needs for change? How do they maintain their resilient thinking? Let’s learn from those who have tried in the past to turn things around in their organizations.

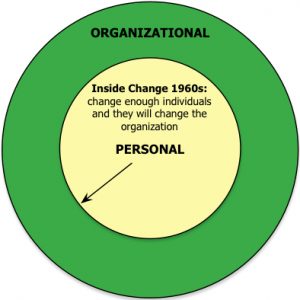

In the 1960s, in the infancy of organization development, managers and experts practiced the notion that in order to change a company’sperformance, you first had to change individual associates in that company.This “inside approach” to change (see graphic) was characterized by training seminars and personal growth experiences. Many people were helped by this approach, but very few organizations actually improved their results as a result of personal approach.

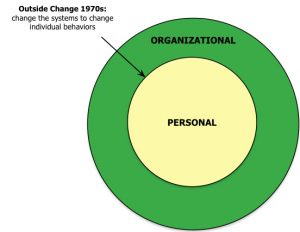

In the 1970s, conventional wisdom called for a “systems approach” by addressing issues such as strategy, structure, reward systems, and work teams. This “outside approach” rewired much of how work was done, but research showed that only 25–30 per cent of these approaches actually improved results. This outside approach to change, or a turnaround, is the dominant method still used today – with the same bottom line as before.

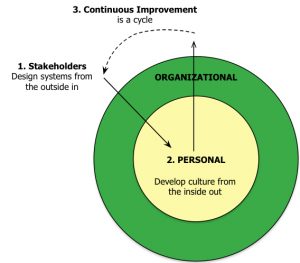

Neither the inside nor outside approaches were completely wrong. As the graphics for these two approaches demonstrate, each of them focused only on one of the circles (the Personal or the Organizational). My work with several corporations has revealed that both of these approaches are important, but the sequencing and connecting of them to the whole system is the secret key that unlocks a true lasting organizational turnaround.

As the structure of this article contends,a turnaround begins with leadership’s vision of what needs to be accomplished.This vision should add value to your customers and other stakeholders.Then the vision should drive the design of processes, systems, and culture aimed at meeting these stakeholder needs. Thus, the first phase of a turnaround is the outside-in approach to organization design.

But people often oppose change, especially if it disrupts their comfort zone for no apparent good reason. Thus, the need for turnaround phase two: you must develop the culture (how people think and act) from the inside out.

When these two phases are repeated periodically to ensure your enterprise is always aligned with evolving stakeholder needs, you achieve the elusive capability for continuous improvement. You may be fortunate enough to experience a number of organizational turnarounds as time and market demands move forward. For example:

When these two phases are repeated periodically to ensure your enterprise is always aligned with evolving stakeholder needs, you achieve the elusive capability for continuous improvement. You may be fortunate enough to experience a number of organizational turnarounds as time and market demands move forward. For example:

- Techno, a manufacturing plant, was underperforming versus its corporate peers. Because this plant was pioneering a new product in the market, company management was reluctant to expand the product across the region.Techno’s leadership team developed a new vision that certainly stretched the capabilities it had demonstrated in the past. But then considerable work was given aligning with the vision by revamping development systems, leadership training, team development processes and scorecards, and proactive relationships with key external stakeholders. This systems approach paid off in the next 18 months as Techno moved into the number one position in the company in all results areas.

Then external changes occurred. Some key leaders were transferred.These leaders were a bit irritated when they heard the new leadership started updating the plant vision. “They don’t need a new vision,” the old leaders said, “they need to keep progressing on the path they are already on.” But the plant far exceeded its earlier accomplishments by (1) addressing key misalignments between it and several external stakeholders and by (2) exporting leaders to staff other plant start-ups that enabled a rapid expansion of the product across the region.These were the two major milestones in its new vision statement. In the end, Techno fueled not one, but two business turnarounds.The first turnaround moved it to the top of the corporate standings; the second turnaround enabled its product to become a regional success.

Conclusion

We can see the need for organizations to accomplish a turnaround – for their organization’s sake, for their associates’ sake, and for their customers’ sake. The past disappointments are not because of the lack of trying. But too many turnaround efforts have focused too narrowly on only pieces of the whole system that needed to turn around. The planners have underappreciated the leadership requirements to mobilize the effort and stay the course until the results match the vision.

Similarly, as the statistics reveal, there are 99 managers who seek an organizational turnaround for every leader who does so successfully. Apply some of the ideas described here to strengthen your own leadership and to design systems capable of lifting the whole organizational system to reach the vision. Do this and you just might be the “one” who succeeds!