Designing for Extreme Alignment From the Outside-In

Here is a design process that builds upon the survival code principles and mindset shifts for extreme alignment:

Step 1: Develop Extreme Alignment With Stakeholders (Internal And External)

The suitability and survival of any organization lies in the eyes of its different stakeholders. The proposition is very straightforward: deliver to the most critical stakeholders what they need most, do it better than competitors, and you will have all the business you want. Failing to do so opens the door for those stakeholders to find better options:

- Investors will look elsewhere for better returns on their investments.

- Customers will try competitors’ products.

- Enterprises that provide superior service will draw away your customers.

- Dissatisfied associates will look for new employment.

Extreme alignment with each stakeholder group begins with your mindset.You must seriously “Think Win-Win” as my mentor Stephen R. Covey has said.You must make it your business to fulfill the stakeholder’s most critical needs. Not necessarily every need, but the ones that would make or break their commitment to you. And they must be able to meet your most critical needs, such as honoring contracts, making timely payments for your products/services, and coming together as partners when problems arise (on either side).

Meeting the stakeholder’s most critical needs may cost you time, money, and resources. This will have an impact on today’s profitability. Some companies try to shortcut their deliverables to boost their own profit picture. But how is their profit picture affected if the dissatisfied customer abandons them altogether? And what message does this send to other stakeholders?

Is this just a philosophical caution? Ask Company Z.

Company Z had been losing market share and profitability for some years. In a desperate attempt to halt the slide, they demanded all suppliers to tear up their business contracts and revise them at no more than 80 per cent of the original, agreed-upon

amount. The suppliers swallowed hard and signed the new contracts.This brought billions of dollars to Company Z’s bottom line that fiscal year.

A few years later Company Z worked with its union to finalize a new union contract. The discussions became very difficult and heated. The union demanded Company Z include even the most specific details in the new contract. Threats were exchanged. In the end, the union called for a labor strike and shut down all of Company Z’s manufacturing facilities. Discussions continued, and the strike finally ended after many, many weeks. The revenues lost during the strike were greater than the money saved from tearing up the suppliers’ contracts.

Do you suppose the union leaders were distrustful of management’s promises to them after observing what happened to the suppliers?

So, survival does depend on how well you fulfill stakeholders’ critical needs. This being so, it seems logical that you would have a stakeholder information system at least as thorough as any financial information system or product research system. What elements would such a stakeholder information system have? How about:

- Clear identification of the results (“deliverables”) each partner should contribute

- Expectations of what I call the “do’s and don’ts” – standards of behaviors when working together

- Resources each partner will dedicate to meet expectations and to deliver the results.

- Monitoring of progress: agreement on how often and in what format to report progress to each other.

What This Looks Like in the Real World: Ritz-Carlton Hotels

No doubt you have heard of the legendary customer service at The Ritz-Carlton Hotel Company, a consistent leader in the hotel industry and the only two-time winner of the Baldrige National Quality Award in the service industry. Though many have heard some Ritz-Carlton stories, very few understand how such extreme alignment to

its guest needs have provided these stories for the past 36 years. Here are the driving forces of such laudable performance:

1. The Credo: notice how it focuses on specific guest needs and associates’ priorities for fulfilling those needs:

2. 18 Core Processes: each core process is designed to fulfill important guest needs derived from the Credo; everything from making a reservation, to any aspect of the hotel stay, to departure – and beyond. All systems, processes, and associate interactions that define the guest experience are supervised by Ritz-Carlton associates themselves.

3. The Bottom Line: excellence in the company’s performance is defined through the eyes of three main stakeholder groups:

- Happy Associates: in an industry where employee turnover averages 100 per cent per year, Ritz-Carlton’s turnover is approximately one third of that average.

- Happy Guests: average occupancy rates at Ritz-Carlton are far above industry average; guest engagement scores are above 90 per cent in Gallup research.

- Happy Owners: every Ritz-Carlton property is owned by a third-party investor. With very few exceptions, these owners are happy with their Return On Investment.

4. Continuous Improvement: each year each hotel recommends how to improve one of the 18 core processes. Submissions come into headquarters and the best ideas are turned into company wide actions. These improvements invariably improve the experience for both guests and associates.

Ritz-Carlton shows us that an outside-in alignment to “make your business my business” enriches the well-being of all stakeholders.

Step 2: Craft Extreme Alignment Between Associates And Their Work

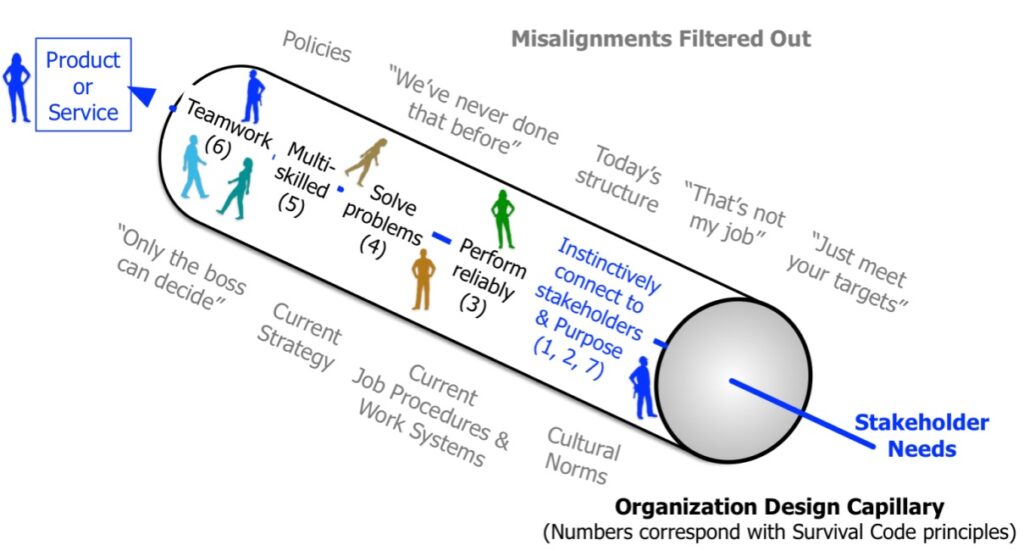

Even the best of stakeholder agreements represents only a statement of good intentions. Success only emerges from how aligned the different players are in making good on their intentions.The process of extreme alignment between associates, stakeholders, and their joint work looks something like this:

- All associates in the organization are aware of and committed to fulfilling their key stakeholders’ needs. The metaphor for this alignment is to “make their business our business.” Making this mantra more than a mere slogan requires extreme alignment of the players’ underlying values, skills, and energy as well as sufficient resources from the entire organization.

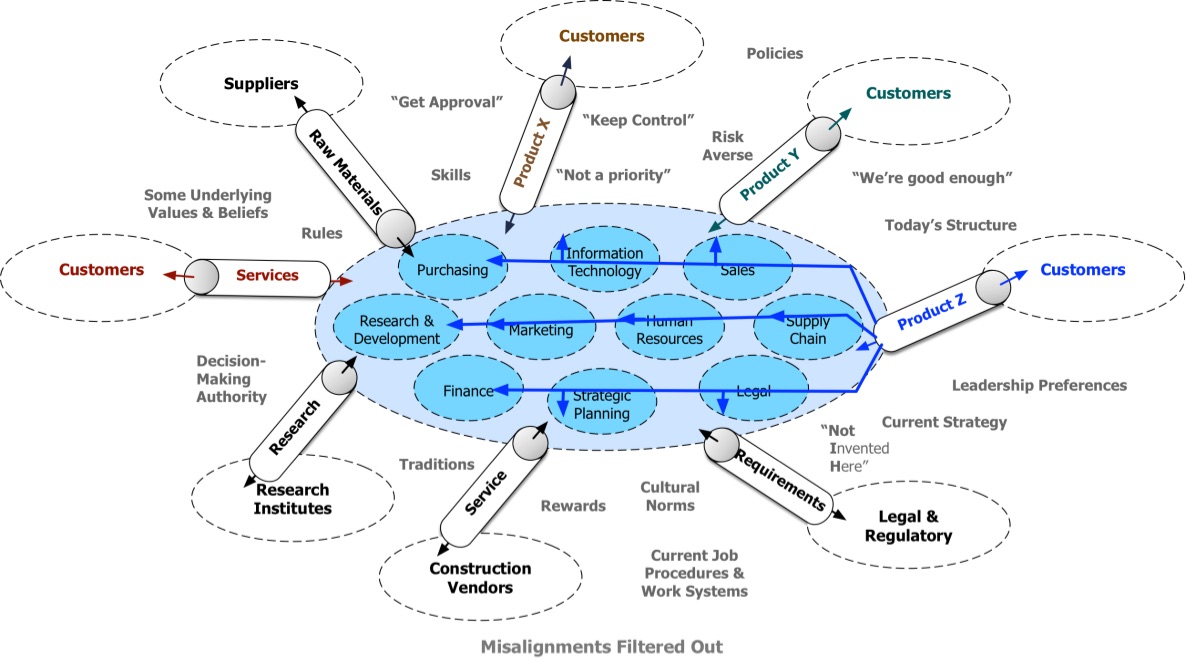

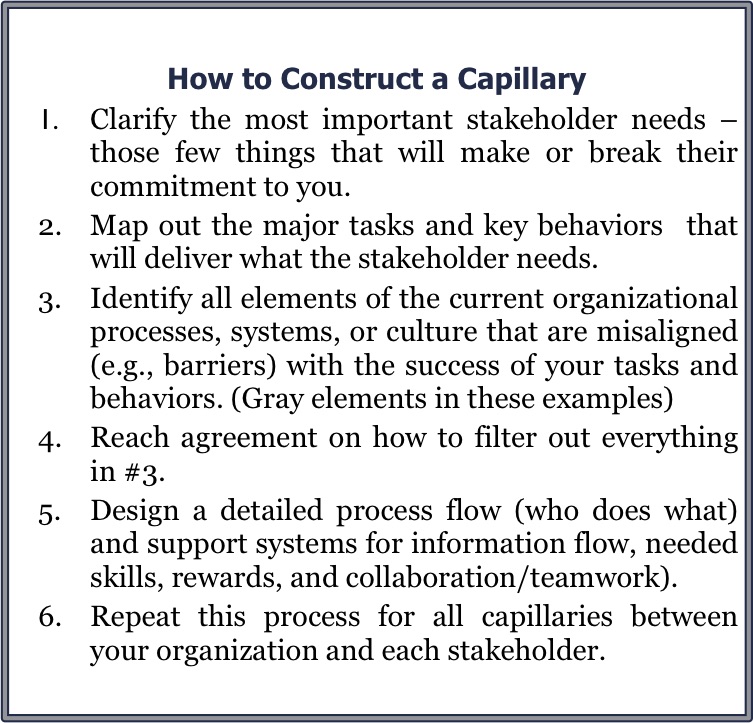

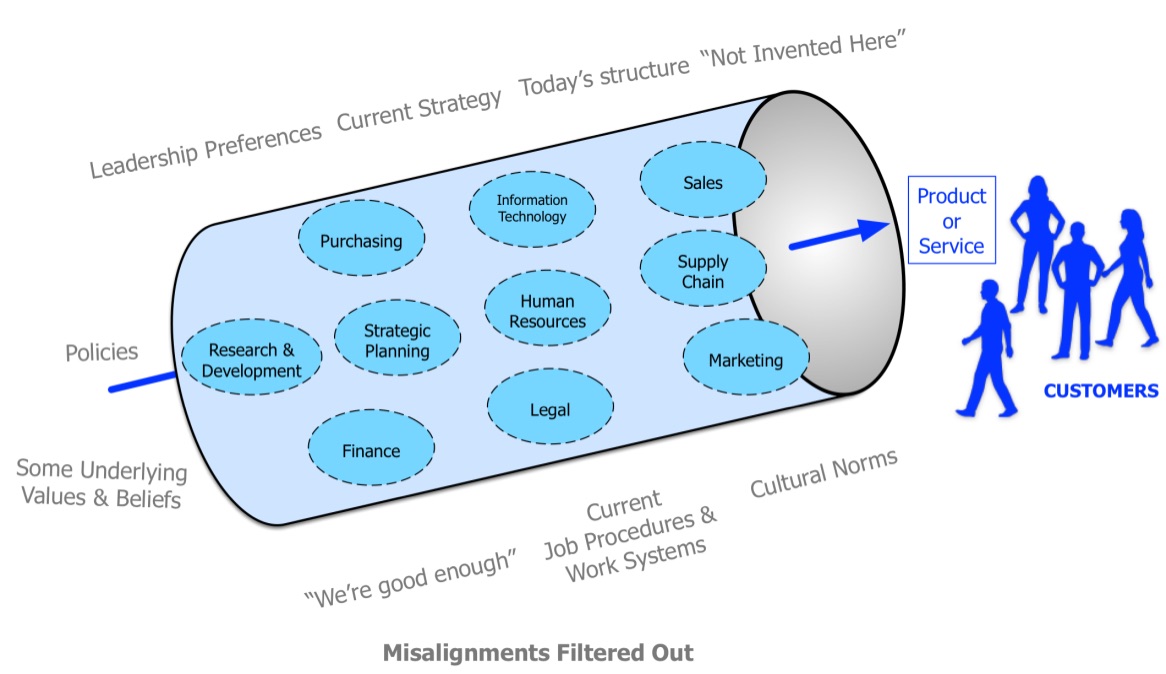

- “Making their business our business” launches a new organization design process. Much organization design work today begins by considering the company’s strategy, its chosen products and services, and then organizes functions, departments, and individual job responsibilities to win in the marketplace.This is an inside-out design process.But the aim to make a stakeholder’s business your business must be approached from the outside-in. Organization designers must shape an Organizational Capillary (like the filtration scientists cited earlier), a designed channel to be “extremely aligned” to fulfill stakeholder needs while filtering out distracting “impurities.”

Here is a graphic representation of how this works:

The output of this “capillary” is a product or service that fulfills the stakeholder’s needs.Any function or activity that tangibly contributes value to this output is channeled through the capillary. Some of these might include:

- Timely, quality interactions and reciprocal feedback with the stakeholder

- Creation of products and/or services that the stakeholder values

- Organizing processes and systems from support functions to core operations and individual tasks to deliver the required outputs.

- The new design must filter out any “impurities” or distractions that might compromise the desired output. Such factors are illustrated in the gray elements of the graphic. For example:

- **Current job procedures and work systems may need to be stopped or revised.

- ** “Top-down” leadership preferences may need to be redesigned to permit skilled, responsible decisions at the point of action.

- **Functional silos may need to be supplemented by cross-functional structures for work that requires a high level of collaboration.

- **Policies or operating rules may need to be revised.

- ** Work culture norms, such as beliefs that “we’re good enough” or “Not Invented Here” may need to be eliminated or upgraded.

- The new design must be supported by training and development systems to equip associates to function competently and effectively in the new organization. Some examples:

- If associates are expected to be able to solve any daily problem they face, they must be given the knowledge, tools, and skills to do so.

- If teamwork and collaboration are imperative for some tasks, some training in collaborative skills might be warranted.

- If high flexibility and responsiveness are required, the development of multi-skilled associates has proven to be essential.

-

Most likely, some new processes and systems between the organization and some stakeholders will need to be designed jointly.

- Generally speaking, the bureaucratic leadership artifacts of yesterday must be retired. Such artifacts as:

-

Control only by supervision

-

Steep hierarchical levels

-

Preoccupation with spans of control

-

Exclusive centralized decision making

- Other bureaucratic artifacts about the organization of work must likewise be retired in favor of swifter, more flexible capabilities. Some of these transitions include:

- “The job” must be upgraded to “our roles” in the spirit of any associate can and will be able to do a number of different things when necessary to deliver the required outputs.

- Sharing some traditional leadership responsibilities to put decision making closer to the points of action.

- Institutionalizing teaming as a way of life to produce 3600 synergistic collaboration

Key Points

- The organization (and each of its subsystems) must address a diverse set of very important stakeholder needs.

- Some of these needs may have the same effect on all subsystems. Common design features may be suitable to address these.

- Some of these needs will impact different subsystems differently. Such subsystems may require different and unique organizational and interaction processes and tools.

How the flow of design “capillaries” affects an organization

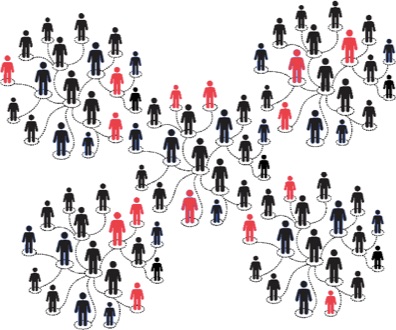

A more simplified view of the previous graphic is to show how one stakeholder’s needs/requirements for the organization should flow through the organization like the bloodstream flowing through the body. (See below.)

- The needs should connect with all subsystems and provoke a conscious reaction of (a) to respond to them or (b) to ignore them.

- Once all actionable needs (from all stakeholders) have been logged into every function, that function should re-posture its purpose and organizational elements to be extremely aligned with those needs.

- Turning up the organizational microscope, the functions must extremely align their response to their stakeholder needs. The best “streaming device” I have seen to deliver such a response is a multi-functional team (a mini-version of the parent organization), specifically designed and outfitted to be extremely aligned with the stakeholder’s needs. Below is a graphic illustration of the this mini-company:

What This Looks Like in the Real World: Leaderless Teams in Silicon Valley

(This is an experience my friend Ord Elliott had in Silicon Valley.) A network storage company (let’s call it StorServ) faced a brutal corporate life-or-death challenge. In six months, a competitor was coming out with a new server that had performance and features that would surely obsolete StorServ’s current product.Although a new product was in the works, their typical product development rollout history was thirteen months from concept to product.

The company was functionally fragmented into many different departments.The next generation product needed an array of new features to meet the next competitive bar. The construction of these new features, however, could not be easily accomplished without dialog and tradeoffs across the functional boundaries.

StorServ formed 25 cross-functional teams composed of hardware and software engineers, along with associates from marketing, operations, and finance. Each team was charged with building one of the features as part of the new product architecture.

The teams’ challenges were: (1) very few individuals on these teams had any leadership experience and (2) to achieve milestones in one team, there might be trade-offs or choices with other teams that would have to adjust to—or perhaps block–in favor of their own objective. How would these teams be able to work together under time pressure successfully and, just as importantly, coordinate and negotiate tradeoffs with the other teams?

Out of desperation came a wild idea: instead of considering the leadership function as one person’s responsibility, why not see if different team members could lead one, two, or even three items?

Most teams identified three or four people who, collectively, could provide the needed leadership. Ironically, the very lack of capable leaders allowed for this unorthodox solution.

These new teams were disconnected from the stable, functional organization that spawned it. This loose network seemed more like a separate company.

The teams correctly determined which of the other teams they needed to interface with. The chosen “connectors” were successful in bridging overlaps and differences to work out practical compromises in the interests of the larger objective.

Three-and-a-half months passed.And they delivered a new superior product! Not only did they surpass their “unrealistic” goal of five months, they absolutely destroyed the previous product development best of thirteen months. Ultimately, they would beat the competitors to the marketplace, and more importantly, save all those jobs.

When done with atomic-scale precision, aligning people, work, and stakeholder needs yields the reality of “The needs of the people and the company are inseparable.”