Introduction

Consider this question: What good does it do to redesign an organization if the changes don’t enable it to survive?

So often we spend our time trying to reshape our organization’s culture, or restructure, or devise a new compensation scheme to fix the crisis of the day. But how often do we examine the whole system of organization in its ever-changing competitive environment and then align organizational elements to survive?

The importance of distinguishing between these two objectives was demonstrated to me at a conference some years ago.A presenter was sharing his company’s experiences with redesigning its operation to compete better against Japanese firms. Following many popular design trends of the day, he outlined how his company had restructured into a team system, initiated a new compensation plan, written a new mission statement, and increased its training budget. At the end of his presentation, I asked the question,“How has your redesign work helped you compete better against the Japanese firms?”

His answer was shocking, “Well, you can’t really compete against the Japanese.”

What good, then, was all of this organization design work?

Market Dynamics Are Constantly Changing

The market and industry dynamics in which we operate are being transformed at a staggering rate. So many work ingredients in the formula are changing so rapidly that people and organizations can scarcely keep up. Some of these ingredients include:

- Global economic changes, societal changes, and new technologies – these are drivers of new and different work compared to that of a few years ago.

- While the technical world is becoming proficient in streaming information, organizations are lagging behind in their efforts to “stream” their work efforts through “pairing” technologies, work tasks, and connecting diverse team members.

- Many processes and systems we have worked with for decades are no longer delivering good results like they used to. Case in point: Author Daniel Pink cites research that shows some new realities about reward systems. The big “aha” of the research: monetary rewards work well for those doing primarily physical tasks. But if the work is cognitive, giving people more autonomy or opportunities for greater mastery are more rewarding benefits than money.

Many contemporary articles in today’s literature attempt to describe formulas for success with new titles or phrases that are merely new packaging for fundamental principles that have been advocated for decades. Dig into them and you won’t find much that is really new.

New packaging of the fundamentals doesn’t ensure survival. Many past efforts have “more or less” addressed the fundamentals for survival.What is required is not an “approximate” alignment, but an “extreme” alignment with these fundamentals.

A Scientific Metaphor

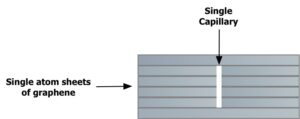

Recent research in the field of capillaries and cavities is a good metaphor for aligning today’s organizations. Materials with tiny capillaries and cavities are used widely in filtration and separation to support our modern lifestyle.

Up to now, charcoal carbon filters have proven to be the most effective at removing chlorine, and other undesirable elements from water. But the molecular structure of carbon is a blend of cavities (cave-like chambers that trap undesirable elements) and capillaries (channels that permit water to be passed on).

One difficulty with the charcoal carbon filter is that all elements must pass through its slow, somewhat meandering process to deliver the desired output.

Other similar filtration materials usually have been found by luck or accident rather than by design.

Until recently it has been impossible to create artificial capillaries with atomic-scale precision.

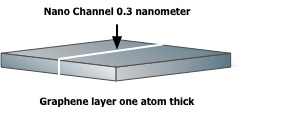

But now researchers Radha Boya and Nobel laureate Andre Geim have made the impossible possible. These researchers have removed strips in graphene (a flat layer of carbon one atom thick) to create Nano channels. These channels can carry fluids or gasses through them to accommodate a single molecule of water at a time, while filtering out salt, viruses, and bacteria that easily attach to water but are too big to fit through the 0.3 nanometer channel.

Stack enough sheets of graphene on top of each other with nano channels precisely removed in each one, and you have a designed channel that is a faster, more direct conduit to allow the desired element to pass through while filtering out undesired elements. But the channel must be designed to be “extremely aligned” to the properties of the materials that will pass through it and to deliver the precise desired output. Approximations (jagged edges, microscopic differences in nano channel sheets’ specifications) won’t get the job done.

This discovery is a big breakthrough in filtration and is being studied by scientists all over the world, especially in China, India, and the UK.

What intrigues me about this study of atomic- scale design is the functional capacity to channel some elements in a targeted direction and to filter out undesirable elements. This is actually a very serviceable definition for designing an organization. Consider for a moment what you might accomplish if you could channel the delivery of your products or services to be “extremely aligned” with stakeholder needs while filtering out distracting “impurities.”

Natural Laws Drive the Need for “Extreme Alignment”

Organizations are living (people) systems that are governed by the same natural laws that sustain living ecosystems in nature.The major challenge is to apply organization design tools with an understanding of the whole system and its context in the competitive industry/environment in which it exists. Without understanding the whole system, your design may “approximate” alignment, but will not be in “extreme alignment” with the natural laws of living systems.

Speaking of whole systems, a 2018 study by professional services company PwC revealed the top concerns of CEOs around the world. The top five concerns were:

- Over regulation

- Terrorism

- Geopolitical Uncertainty

- CyberThreats

- Availability of Key Skills in the Marketplace

These five concerns are part of the ecosystem of today’s businesses. But how many of these can a CEO control? None! How can they escape their perils? Survival comes not by controlling external dynamics, but by understanding them and aligning your resources to respond powerfully. Forests respond and rebuild themselves from devastating fires because natural laws govern their recovery processes.

I call some of these natural laws The Organizational Survival Code because they explain why an organization either does or does not survive over time.The headings below are confirmed by natural scientists as being key to an ecosystem’s survival.The specific point under each heading is an organizational application. In a nutshell, here is the Organizational Survival Code:

- Ecological Order: strategize to fulfill the most important needs and expectations of your key stakeholders.

- Purpose: develop a compelling purpose and strategy so that each member instinctively acts to fulfill it.

- Steady State: design work processes that reliably and consistently deliver high quality outputs.

- Mobilization: solve problems at their source.

- Complexity: build more self-sufficient, flexible, multi-skilled people and work units.

- Synergy: develop true partnerships with all stakeholders so that you always enjoy a competitive advantage.

- Adaptation: re-strategize and redeploy your resources in the midst of external changes to stay atop the lifecycle.

The implication of these seven principles is they are the standard for survival.The more challenging the environmental context, the more “extreme” the alignment with them must be.

For instance, to craft a company mission statement is an approximate alignment with “Purpose” in the above list. Extreme alignment means that individuals in all areas and at all levels intrinsically channel their efforts to fulfill the mission.Their channeling filters out dysfunctional and distracting traditions, obsolete assumptions, uninformed judgments from on high, or ideas like “we are good enough.”

Similarly,an organization chart may be in approximate alignment with “Mobilization.” But “atomic-scale precision” alignment means that individuals, regardless of where they fit in the organization chart, have the knowledge, skills, and commitment to solve any daily problem they face in their work.

And so forth.

In every industry today, there are leading companies who may not measure up to every one of these survival standards.As the environment changes and as competition becomes more challenging, these leaders must become extremely aligned in each of these seven areas or risk falling. Horst Schulze, the founding president of the Ritz-Carlton Hotel Company, would say after reading a stack of guest feedback letters,“We are by far the best hotel in the industry. But we are the best of a bad lot.”

Don’t take my word on all of this. Look at the numbers! Compare the Fortune Global top 100 companies lists for the past half century. In every decade approximately 50 per cent of the 100 have fallen off the list. Some of these powerful companies have even disappeared, either by being swallowed up by another enterprise or vanishing altogether.

A word of caution:the terms“extreme alignment” and “atomic-scale precision” should not be interpreted as a need for traditional re-engineering or the use of organizational micrometers. These labels drive one to think organizational improvements can be accomplished by the better design of technical things only. Redesigning a technical thing focuses only on that thing’s function. Synergy focuses on “intangibles” such as relationships between people in stakeholder groups in the ecosystem. Extreme alignment requires both technical advances and greater synergy between human stakeholders

For example: because people are so diverse, atomic- scale precision may mean that no two teams are designed exactly the same; leadership, support, decisiveness, and objectives may need to be different for different groups and individuals. Policies or grand organizational schematics alone cannot deliver atomic-scale precision for relationships.

What This Looks Like in the Real World: The Stora Enso Company

Stora Enso is generally regarded as the oldest industrial company in the world. A document in 1288 first mentioned the existence of Stora Kopperberg, a Swedish copper mining enterprise. In medieval times this company supplied copper for many purposes, most notably the construction of ships and cathedral steeples throughout Europe.

Through the centuries as natural resources waned and technology and lifestyles evolved,Stora’s business has adapted successfully from mining to a renewable materials company. It merged with Finland’s Enso Oyj in 1998 and today produces renewable products such as consumer board, packaging solutions, biomaterials,, wood products, and paper. Through each of its adaptive phases, Stora Enso has revised its purpose, established a steady state to produce new products, mobilized resources, developed complex skills in new businesses, and synergized with new partners to enable it to stay on top.

The natural resources in Stora’s 13th century copper mines have long since been exhausted, but the company lives on, with 26,000 associates in more than 30 countries still making a significant contribution to the quality of life for many of us.

As Stora Enso’s experiences show:“extreme alignment” and “atomic-scale design” of organizations must be focused uncompromisingly on the whole system’s survival and the required human interactions that will sustain it.

New Mindsets for Survival

I advocate an organization design process that incorporates the survival code principles and moves from the outside (stakeholders’ key needs) to the inner workings of the organization.You focus first on stakeholders’ key needs because this puts you in touch with the whole ecosystem and the current order of things in which your organization must exist. This outside-in design process embodies a number of mindset shifts from traditional bureaucratic assumptions about organizing work. Some of these shifts include:

- Moving beyond performance standardization to being driven by purpose and strategy tied to survival requirements in the “order of things.” Certainly, work processes need to be as efficient and free- flowing as possible. Process and work standards are important. But these should never dictate to the organization what is or is not possible (or permissible) to fulfill important, changing stakeholder needs. Stating,“Our systems aren’t set up to do the things you require” is a speedy and sure way to lose a stakeholder’s business.

As former Intel CEO Andy Grove said, “Whatever can be done, will be done. If not by incumbents, it will be done by emerging players. If not in a regulated industry, it will be done in a new industry born without regulation. Technological change and its effects are inevitable. Stopping them is not an option.”

-

Moving beyond task specialization to thinking of all tasks as part of a process. The bureaucracy model broke down a work process flow into discrete individual “jobs” that average people could handle. Thus, emerged assembly lines and similar innovations that reduced work to the smallest repeatable set of motions. While these technical breakthroughs did elevate organizational performance significantly at first, they also unintentionally moved one’s line of sight from fitting into the order of things to accomplishing only individual work objectives. In the past century other needs and high-tech tools have led to the imperative of optimizing whole processes, rather than each discrete step.

-

Moving beyond efficiency to self- sufficiency. The mechanical model of centralized control units as the governing force has likewise been supplanted by the notion of self-sufficient units: individuals, teams, and business units that have virtually every resource needed to manage the daily work.

-

Moving beyond hierarchical thinking to thinking functionally. Rather than coping with increasing ecosystem complications by adding layers of decision-making hierarchies, the newer version focuses on a pragmatic sharing of decision-making: who should make decisions based on the issues they face every day.

-

Moving beyond spans of control to control at the point of action. Functionally-based decisions rely on two criteria to make it work: one’s knowledge and experience with the issues that must be decided.This is not a call for “pushing all decisions to the lowest possible level.” Based on one’s knowledge and experience base, a major systemic decision with global implications may be competently addressed only by the CEO or members of the C-suite. But operational decisions, or customer account decisions, under this principle, would be handled best by those closest to these points of action.

You will see these mindset shifts in evidence in Part II as we walk through the steps of this “outside-in” design approach.