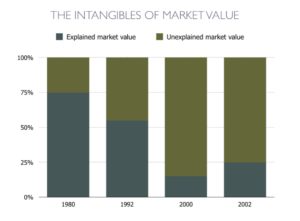

Organizational culture is a topic that continues to polarize the corporate world. My definition of culture is very simply “the way we do things around here.” And that is the driver for every good and bad result a corporation delivers. Finance Professor Baruch Lev of New York University has conducted research showing that intangibles (as culture is often thought of) are now the most dominant factors in determining a company’s share price. Past results and tangible assets accounted for 90 per cent of a company’s share price in the 1960s, their influence has shrunk to less than 40 per cent today.

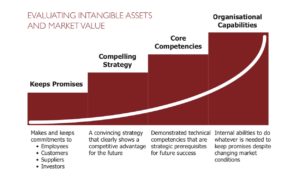

It is a company’s culture that fuels the dominant drivers of share price today: a competitive strategy, leadership, innovation, collaboration, and speed to change with evolving market dynamics, just to name a few. Here are two examples (disguised names for the first) of how organizational culture has affected business results.

“What people really harbour in their hearts and minds are

the roots of those actions that play out every day in

the workplace.”

The Alpha Pharmaceutical Company acquired the Bravo Company with two clear objectives in mind:

First, acquire Bravo’s scientific knowledge base to further develop leading edge compounds and products and

Second, grow the Alpha business, in terms of sales volume and profitability, in the process.

Scientifically and business-wise, this deal looked like a perfect fit. The two companies had complementary scientific skills and each had a record of consistent goal achievement. Bravo Company had some winning products in a category that Alpha was deeply interested in. If you talked to Alpha’s HR people, they would tell you the merger was handled perfectly. However, something was amiss, because nine of the 12 Bravo executive team members left the company in the first year along with 15 of the 20 vice presidents. Six of these VPs were also key science leaders.

Underneath the surface, at a level no one had time to address, were issues of mis- trust from Bravo members toward Alpha. It was unclear how the different projects were to proceed with two sets of research protocols, different approval processes, and Alpha’s reputation for a heavy top-down management style. The suspicions about “how we are going to do things around here” drove away many key Bravo leaders.

In the second example, when Procter & Gamble purchased the Richardson Vicks Company some years ago, the shaping of a common culture led to great success. In Asia, for example, the former rivals were expected now to be teammates in 11 coun- tries. Todd Garrett, the division vice-president, faced the dilemma of uniting these warring factions to grow the business. Garrett also was given a profit target for the division that greatly exceeded the best collective results the two entities had ever produced. Gathering key leaders from the 11 countries, plus leaders of his corporate staff, he started working with his team on important strategy and business issues. They reached consensus and developed real commitment for a division strategy, mission, and core values.

These priorities and explicit values and beliefs were the first pillar of the new Asia Pacific division’s culture.After all, what people really harbor in their hearts and minds are the roots of those actions that play out every day in the workplace.The new executive team members built trust in each other in these work sessions and then began working on the second cultural pillar: the redesign of key processes and systems so that the different business units and functions could naturally collaborate on their agreed-upon priorities. One of the new structures was a system of cross-function- al/geographical business teams designed to roll out new products in all countries simultaneously. Each general manager led a business team for one of the division’s major brands. Expectations were exchanged and agreed among the subsidiaries and between the subsidiaries and division headquarters. The organization now had a common way of doing things that everyone agreed would build the business.

In the first full fiscal year following all this organizational work, the Asia Pacific Division relied on the two cultural pillars it had created, exceeded its “impossible” profitability goal, and became the most profitable division in all of Procter & Gamble.

As these examples show, paying attention to culture does matter to the business. Involving the key players in shaping and maintaining the cultural pillars can yield high performance rather than great disappointment.

FOUR KEYS TO CULTURE

- Culture is “the way we do things around here.”

- Culture drives every good and bad result a corporation produces.

- Two pillars shape and support a work culture: Underlying values and beliefs; and work processes and systems.

- The involvement of key leaders in shaping the two cultural pillars makes all the difference to the bottom line.

Managers and HR who demonstrate the following competencies will become leaders who enable their organizations to survive – and thrive – in today’s challenging world:

- The competency to diagnose

- The competency to apply organization theory

- The competency to design highly effective organizations

Source:The Organizational Survival Code: Designing Your Organization To Get The Results You Want

(Infographic source: Baruch Lev, Intangi- bles: Management, Measurement, and Reporting, Bookings Institute Press, 2001)

Originally published in Inside HR http://www.insidehr.com.au/why-culture-matters-to-business/