“There is the Moral of all human tales;

‘Tis but the same rehearsal of the past.

First Freedom, and then Glory—when that fails,

Wealth, vice, corruption—barbarism at last.

And History, with all her volumes vast,

Hath but one page.”

—Lord Byron

Many corporations (and industries) are struggling to survive in a rapidly changing global marketplace. While we may think our struggles today are unique, a review of the big picture of organizational lifecycles reveals that we are in the middle of the latest iteration of a consistent pattern of business dynamics that has defined survival for centuries.

As we consider the big picture, think about what the following companies have in common:

- Cambria Steel

- Guggenheim Exploration

- Lehigh and Wilkes-Barre Coal

- Intercontinental Rubber

- Schwarzchild and Sulzberger

- Central Leather

Each of these institutions was one of the top 100 U.S. firms in 19091, but none exists today as an independent entity. They are either out of business or a very minor player in some larger corporation. Some were quite large in their glory days (Central Leather was number seven on the 1909 list). Unfortunately they were not able to maintain their success. In a few management generations they have disappeared. These six are certainly not unusual: of the top 100 U.S. industrial firms in 1909, only 14 are still in the elite group today. Only 23 are still around at all!

To update this picture I considered today’s Fortune Magazine’s Global Top 100 list. The resulting table is most instructive:

Fortune’s Top 100 Global Companies2 |

|

|

2020 Leaders Wal-Mart (1) Sinopec Group (2) StateGrid (3) China National Petroleum (4) Royal Dutch Shell (5) Saudi Aramco (6) Volkswagen (14) BP (8) Toyota (10) Microsoft (47) Carrefore (98) Nestlé (82) |

Casualties of the 2000s Mitsubishi Boeing Credit Suisse Unilever Sears Roebuck DuPont Philips Electronics Hypovereinsbank Enron BASF Motorola Procter and Gamble |

The left column lists some representative leaders in the Global 100. The right column identifies some well-known companies who fell off of the list during the decade of the 2000s. These companies were not alone. In fact, 54 of the Top 100 fell of the list during the 2000s. Going back to the original list of 1909, a review of the Top 100 during the decade 1909-1919 shows 59 of those companies fell off the list. So, we can see that regardless of the era, staying on top of the pack is hard to do.

Consider further the reasons the companies fell off the list from 1909-1919:

- Changing economic conditions

- Mergers and acquisitions

- Emergence of new technologies.

So what has changed in 100 years? Not much. Roughly 50% of the Top 100 fall within 10 years for the same fundamental reasons. This common pattern for the past century indicates there are some systemic forces at play here, not just a series of coincidences or random events.

AN ENDANGERED SPECIES

The struggle for life isn’t something peculiar to large corporations. The Office of Advocacy of the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) reports that 99.8 percent of new employer establishments are small firms. The 2008 Bureau of the Census report for the SBA indicated 64 percent of new firms survived two years, 45 percent survived five years, but only 29 percent http://cialis7pharmacy-online.com/ survived 10 years.

ORGANIZATIONAL LIFECYCLES

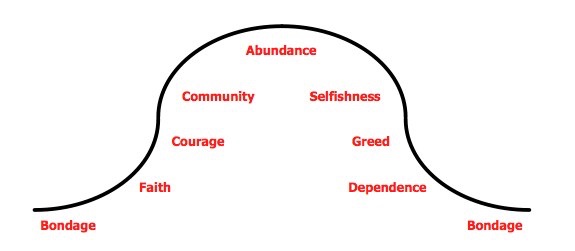

The common pattern from the Top 100 research and the SBA findings is illustrated by this lifecycle graphic. Though one organization may extend its peak phase more than others, most organizations’ bottom line over time looks like this familiar bell-shaped curve:

The lifecycle tells us that whenever people come together, certain dynamics tend to emerge. They unite themselves and grow. Then something happens and they decay over time. Yet organizations are the only living systems that have the potential to live on indefinitely. They don’t have to follow the up-and-down slope of the lifecycle.

In order to know what to do to extend an organization’s lifecycle, we first need to better understand its dynamics. What accompanies an organization’s rise to peak performance? What drags it down? What must leaders keep in mind if they are to stand the test of time? To answer these questions, let’s consider two organizational applications—the lifecycles of civilizations and product innovations. Both are extremely relevant to our present society and global economy. My intent in reviewing these lifecycles is not to make you a social anthropologist or research scientist. Examining their common patterns can help us better understand the natural laws and principles that govern both the ascent and descent of complex organizations. What follows is a summary of thousands of years of human experience as documented by renowned historians. As you read this material, see if you can determine why, as Arnold Toynbee said, “Nothing fails like success.”

LIFECYCLES OF CIVILIZATIONS

The world’s great civilizations such as those in Sumer, Egypt, India, Greece, Rome, China, and Mesoamerica all share a common lifecycle: they started from almost nothing, flourished, declined, and then either disappeared or lingered on as shadows of their former selves as others overtook them. German historian Robert Münzel summed it up best, “Great nations rise and fall—the people go from bondage to spiritual faith, from spiritual faith to great courage, from courage to liberty, from liberty to abundance, from abundance to selfishness, from selfishness to complacency, from complacency to apathy, from apathy to dependency, from dependency back again into bondage.”

Building on this description, I offer this lifecycle with the following nine stages:

THE CIVILIZATION LIFECYCLE

- Bondage: all great civilizations start in bondage to others and either overthrow another group or emigrate to a new home. One key to moving out of bondage is tribal loyalty. The tribe is one, characterized by equality of duty.

- Faith: moral or religious faith has accompanied the early rise of each civilization. The element of faith provides an overarching value system to which individual desires are subordinated.

- Courage: all members courageously pursue the group’s objectives to protect themselves from enemies and to expand their culture.

- Community: city-states often expand the tribal loyalty to ever-wider circles of followers. Common values make citizenship a personal and fulfilling experience even as the population grows.

- Abundance: each civilization reaches a point where it becomes the envy of its neighbors. Abundance means there is plenty for everyone; that the quality of life is high for most people and not artificially constrained.

- Selfishness: The overarching set of values dissipates, enabling the people to glorify themselves and gratify their own desires. Divisions in beliefs and wealth become more pronounced. Cooperation breaks down.

- Greed: the quest for self-gratification leads to greater materialism and an ever increasing escalation of exploiting other groups for the benefit of a select few. Said one historian, “Wealth corrupts, not immediately, but invariably.”

- Dependence: inequality grows with greed, bringing a division between an advantaged minority and a deprived majority. Ironically, the civilization becomes dependent on its weakest link for further progress.

- Bondage: weakened civilizations eventually give way to other groups. Thus the lifecycle comes full circle: from bondage to bondage; or, in Byron’s words, “a rehearsal of the past.”

From the writings of Will and Ariel Durant, Emile Durkheim, Neville Kirk, Albert Schweitzer, Adam Seligman, Pitirim A. Sorokin, Oswald Spengler, Alexis de Tocqueville, Arnold Toynbee, and George M. Wrong emerge the following characteristics of a declining civilization:

WHAT BRINGS DOWN A CIVILIZATION?

- A declining sense of community and national pride (evidenced by political apathy) as people become more concerned with only their own private affairs [selfishness]

- A preponderance of great cities

- A worship of money and material wealth [greed]

- Religious values replaced by disparate and contending secular values and a resulting moral confusion

- A lack of emphasis on the family, marriage, and the proper training of children, leading to further moral and social fragmentation

- The rise of dictators

- A cumulative weakness and chaos in the social fabric that leaves the population open to exploitation and/or decimation [dependence/bondage]

The dynamics of this civilization lifecycle are profound because they transcend individual people, cultures, and even epochs of time. Every civilization is in fact an organization—a group of people working toward some common purpose over time. Pause for a moment and think of your organization as if it were one of the great civilizations. At which point in this lifecycle does your organization find itself? Are you ascending, on top, or sliding downhill? Do these attributes describe where your culture has come from, where it is now, and where the current trends will lead you?

THE PRODUCT LIFECYCLE

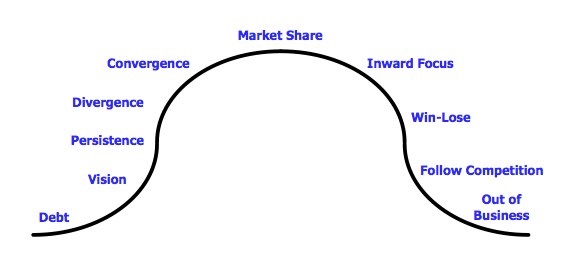

The civilization lifecycle closely resembles another lifecycle—that of the product innovation process. The rise and fall of today’s industrial organizations are due to dynamics that are very similar to those of civilizations. The lifecycle of developing innovative goods and services looks like this:

THE PRODUCT LIFECYCLE

- Debt: The initial context for all innovations is debt, meaning they are dependent on other organizational resources for their sponsorship and execution.

- Vision: Every innovation is sparked by a vision of a better solution (product, technology, or service) to someone’s need. The computer and overnight courier services both began as some individual’s vision of a better world.

- Persistence: Persistence is required by the innovator (often referred to as a product champion) to move the vision to reality against a tide of opposition from the status quo.

- Divergence: This stage calls for experimentation to test the validity of the concept by exploring different alternatives without prematurely judging any as “good” or “bad.”

- Convergence: out of the many options previously explored, a single prototype is selected to introduce into the market place. Now all of the organization’s departments must converge for the product launch.

- Market Share: A period of growth. The market evaluates the new innovation and determines its relative value compared to other available offerings. Abundance follows when the desired market share is realized.

- Inward Focus: Prosperity brings with it a greater emphasis on internal issues: production costs, economies of scale and standardization to minimize the cost of expansion and stabilize the product’s quality and reliability.

- Win-Lose Strategy: as others imitate the new innovation, the focus subtly drifts toward the competitive battle and away from the customer. Win-Lose strategies emerge, attempting to maximize self-interests vs. competition.

- Follow Competition: the inward focus, at a time when competing products are introduced and consumer expectations are being reshaped, results in a loss of the competitive edge. The innovator now becomes a follower.

- Out of Business: the product dies or is replaced by a newer form. This newer form may come from within its own organization or from competition.

Think of how we got the light bulb, penicillin, the newest electronic invention and countless other items that contribute to our standard of living. In each case the product lifecycle dynamics have been evident. Think further about companies, products or services that have become obsolete. Again the lifecycle has been conspicuous as carriages gave way to automobiles, phonograph records have been largely replaced by compact discs, streaming and iTunes, and conventional mail services have been displaced largely by the internet.

Again I invite you to place your own product or service where you think it fits today on the product lifecycle. Are you just approaching the desired market share, already at the top, or falling from where you used to be?

Consider for a moment the common threads revealed in these two lifecycles—and what lessons you can apply from them to your own situation:

The similarities are striking and pose some serious questions. Why is it that with all our technical advances, with our unparalleled capacity to learn and store knowledge, with the coming of reengineering, balanced scorecards, quality and reliability management and sophisticated strategic planning methods—why is it with all this going for us we are unable to build organizations that can hold up over time? One wonders if any system can survive more than a few decades…

There is a light at the end of this tunnel. Organizations do have the potential to “jump the curve” and avoid the downward plunge. See the related article on this blog “The Organizational Survival Code” in which I explore the other half of the big picture—the survival code that will enable your organization to break out of the lifecycle’s fatal spell.

1A. D. H. Kaplan study in Big Enterprise in a Competitive System, Brookings Institution, 1954

2Fortune Magazine’s list of the 500 largest global companies, ranked by revenue, 2009 and 2020