The bottom line of leadership is that leaders have followers, not just subordinates. However, a leader’s ultimate success is tied to his/her ability to deliver results. Whether you are in business, government, education, or in a volunteer agency, leaders—and organizations—haven’t survived in any age unless they achieved some critical, expected results. With this in mind, consider what the following organizations all have in common:

-

- Cambria Steel

- Guggenheim Exploration

- Lehigh and Wilkes-Barre Coal

- Intercontinental Rubber

- Schwarzchild and Sulzberger

- Central Leather

Each of these institutions was one of the top 100 U.S. firms in 1909, but none exists today as an independent entity. They are either out of business or a minor player in some larger corporation. Some were quite large in their glory days (Central Leather was number seven on the 1909 list). Unfortunately they were not able to maintain their successful beginning. In a few management generations they have disappeared. These seven are certainly not unusual: of the top 100 U.S. industrial firms in 1909, only 14 are still in the elite group today. Only 23 are still around at all! On the other hand, think about what the following corporations have in common:

-

- U.S. Steel (now USX)

- I. Dupont De Nemours

- Eastman Kodak (last listed in 2012)

- Standard Oil (now Exxon)

These companies were also in the Top 100 in 1909 and they (or the organization of which they play a leading role) are still there based on the latest Fortune Magazine list of the top 500 Industrial firms. But even those in today’s top 100 are anything but secure. Each of the five companies listed above has been undergoing serious business shakeups and downsizing in an attempt to remain competitive in the global market. And other giants such as General Motors, IBM, and Sears have experienced severe economic problems in recent years as profits have been down and thousands have lost their jobs. They are straining to do more with less just like everybody else.

The struggle for life isn’t something peculiar to large corporations. What about the small enterprises that enter the global market’s competitive field every day? Research indicates that approximately one million people in the United States start their own businesses each year. Unfortunately, by the end of the first year at least 40% of them will be out of business. And more than 80% of the small businesses that survive the first five years will fail in the second five. Is this what the global market will be known for: creating countless shooting stars who burst onto the scene and then fade as rapidly as they appear?

These alarming trends aren’t just in businesses. Budget cutters are trimming whole departments in government. Schools from kindergartens to universities are scaling back as the educational structure reshuffles. Everyone is looking for ways to deliver more with less.

ORGANIZATIONAL LIFE CYCLES

Both the Top 100 companies and the small entrepreneurial businesses—indeed all organizations—share a common life cycle. Though one organization may extend its peak phase more than others, most organizations’ bottom line over time looks like this familiar bell-shaped curve:

The life cycle dynamics tell us that whenever people come together, certain dynamics tend to emerge. They unite themselves and grow. Then something happens and they degenerate over time. Yet organizations are the only living systems that have the potential to live on indefinitely. They don’t have to follow the up-and-down slope of the life cycle.

Perhaps you now have a new appreciation for the title of this book. Leadership for the Ages offers the potential to extend your organization’s life cycle through the Global Age and beyond. That doesn’t necessarily mean perpetuating everything you are doing today. It may require many changes and evolutions over time, but Leadership for the Ages is about doing what is required for your organization to be alive and healthy for generations to come.

In order to extend an organization’s life cycle, we first need to better understand its dynamics. What accompanies an organization’s rise to peak performance? What drags it down? What must leaders keep in mind if they are to stand the test of time?

To answer these questions, let’s consider two organizational applications—the life cycles of civilizations and product innovations. Both are extremely relevant to our present society and global economy. My intent in reviewing these life cycles is not to make you a social anthropologist or research scientist. Examining their common patterns can help us better understand the natural laws and principles that govern both the ascent and descent of complex organizations. What follows is a summary of thousands of years of human experience as documented by renowned historians. As you read this material, see if you can determine why, as Arnold Toynbee said, “Nothing fails like success.”

LIFE CYCLES OF CIVILIZATIONS

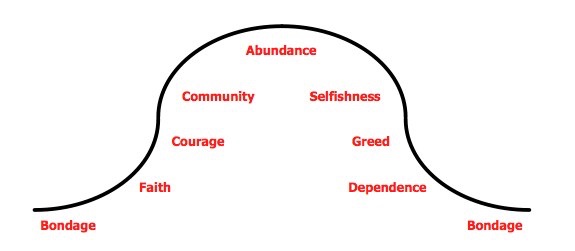

The world’s great civilizations such as those in Sumeria, Egypt, India, Greece, Rome, China, and Mesoamerica all share a common life cycle: they started from almost nothing, flourished, declined, and then either disappeared or lingered on as shadows of their former selves as others overtook them. Robert Muntzel summed it up best, “Great nations rise and fall—the people go from bondage to spiritual faith, from spiritual faith to great courage, from courage to liberty, from liberty to abundance, from abundance to selfishness, from selfishness to complacency, from complacency to apathy, from apathy to dependency, from dependency back again into bondage.” Building on this description, I offer this life cycle with the following nine stages:

1-Bondage: all great civilizations start in bondage to others and either overthrow another group or emigrate to a new home. One key to moving out of bondage is tribal loyalty. The tribe is one. There is no dissent. There is democracy, but it is characterized not by freedom of opinion and dissension so much as by equality of duty.

2-Faith: moral or religious faith has accompanied the early rise of each civilization. The element of faith provides an overarching value system to which individual desires are subordinated.

3-Courage: all members courageously pursue the group’s objectives to protect themselves from enemies and to expand their culture beyond its initial boundaries.

4-Community: city-states often expand the tribal loyalty to ever-wider circles of followers. Though the population may be quite large, the common values make citizenship a personal and fulfilling experience.

5-Abundance: each civilization reaches a point where it becomes the envy of its neighbors. Abundance means there is plenty for everyone; that the quality of life is high for most people and not artificially constrained.

6-Selfishness: after arriving at the pinnacle, unfortunately, most of the great civilizations have also followed a predictable path to ruin. The people begin to be selfish rather than courageous in defending their cause. Subtly the power of moral or religious faith diminishes. There is no longer an overarching set of values, freeing the people to glorify themselves and gratify their own desires. Divisions in beliefs and wealth become more pronounced. Cooperation breaks down; the central power of the state is weakened.

7-Greed: the quest for self gratification leads to greater materialism, colonialism, and imperialism—an ever increasing escalation of exploiting other groups for the benefit of a select few. Social problems grow such as crime, family break ups and poor leadership. Younger generations lack social concern. In the words of one historian, “Wealth corrupts, not immediately, but invariably.”

8-Dependence: since inequality grows with greed, each civilization has found itself divided between an advantaged minority and a deprived majority. As this majority grows, it slowly begins to restrain the progress of the privileged elite. The majority ways of speech, dress, recreation, feeling, judgment, and thought infiltrate upward in society. Civilization remains only as strong as its weakest link.

9-Bondage: weakened civilizations eventually give way to other groups. Thus the life cycle has come full circle: from bondage to bondage; or, in Byron’s words, “a rehearsal of the past.”

“Throughout the history of civilization, societies have been conquered by barbarians whenever they grew weak,” writes historian Charles Brough. “The inescapable conclusion has been that there was a strength in the social structure that enabled them to conquer more civilized people. This in turn has led to the conclusion that a civilization that could resist invasion or could even conquer barbarians must have had a social structure similar to that of the barbarians.” Note that Brough is saying it is the strength of the social structure (organization, culture) that explains why civilizations rise or fall.

From the writings of Will and Ariel Durant, Emile Durkheim, Neville Kirk, Albert Schweitzer, Adam Seligman, Pitirim A. Sorokin, Oswald Spengler, Alexis de Tocqueville, Arnold Toynbee, and George M. Wrong emerge the following characteristics of a declining civilization:

-

- A declining sense of community and national pride (evidenced by political apathy) as people become more concerned with only their own private affairs [SELFISHNESS]

- A preponderance of great cities

- A worship of money and material wealth [GREED]

- Religious values replaced by disparate and contending secular values and a resulting moral confusion

- A lack of emphasis on the family, marriage, and the proper training of children, leading to further moral and social fragmentation

- The rise of dictators

- A cumulative weakness and chaos in the social fabric that leaves the population open to exploitation and/or decimation [DEPENDENCE/BONDAGE]

The dynamics of this civilization life cycle are profound because they transcend individual people, cultures, and even epochs of time. Each of these civilizations can be likened to an organization—a group of people working toward some common purpose over time. Pause for a moment and think of your organization as if it were one of the great civilizations. At which point in this life cycle does your organization find itself? Are you ascending, on top, or sliding downhill? Do these attributes describe where your culture has come from, where it is now, and where the current trends will lead you?

THE PRODUCT LIFE CYCLE

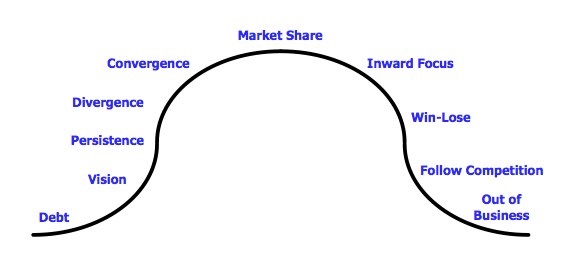

The civilization life cycle closely resembles another life cycle—that of the product innovation process. The rise and fall of today’s industrial  organizations are due to dynamics that are very similar to those of civilizations. The life cycle of developing innovative goods and services frequently looks like this:

organizations are due to dynamics that are very similar to those of civilizations. The life cycle of developing innovative goods and services frequently looks like this:

1-Debt: The initial context for all innovations is debt, meaning they are dependent on other organizational resources for their sponsorship and execution.

2-Vision: Every innovation is sparked by a vision of a better solution (product, technology, or service) to someone’s need. The light bulb, the computer, and overnight courier services all began as some individual’s vision of a better world.

3-Persistence: This vision leads a product champion to go through the arduous incubation period of product development. Persistence is required by the innovator to move the vision to reality against a tide of opposition from the status quo.

4-Divergence: the search for the right means to achieve the product vision results in a period of great uncertainty in which many different paths may be explored. This stage calls for experimentation to test the validity of the concept and to choose an operational prototype. An important attribute in this stage is the ability to explore different alternatives without prematurely judging any as “good” or “bad.”

5-Convergence: out of the many options explored in stage four, a single prototype is selected to introduce into the market place. Now all of the organization’s departments must come together to make the introduction successful. This is a brief period of stability as product and production processes are standardized, marketing strategies are chosen, and early market responses are closely monitored.

6-Market Share: A period of growth. The market evaluates the new innovation and determines its relative value compared to other available offerings. Abundance follows when the desired market share is realized.

7-Inward Focus: The downward spiral for products and services is not unlike that of the great civilizations. Following a successful debut in the market, every innovation has slowly faded from the top. There are several reasons for this gradual decline. First, prosperity brings with it a typically greater emphasis on production costs and economies of scale. This, in turn, increases pressure to standardize production to minimize the cost of expansion. The frequent result of all these forces is to infect the innovators with “Internal Myopia,” meaning they stop focusing on the external market needs and became preoccupied by their own concerns. This causes them to lose touch with the market at a crucial moment, for the introduction of a real innovation inevitably promotes a whirlwind of competitive activity. Competitors begin to imitate and improve upon the new innovation. Customers’ preferences may be reshaped and raised as a result.

8-Win-Lose Strategy: as time passes the market becomes established and the product is standardized. Competition’s innovations are still unproven; new customer needs are unexpressed. Mass production prevails and costs dominate the competitive scene. There is little innovation in this stage beyond superficial product differentiation as the strategic focus subtly drifts toward the competition and away from the customer. Continuing this trend leads to Win-Lose strategies that attempt to maximize self-interests at the expense of competition.

10-Out of Business: the product dies or is replaced by a newer form. This newer form may come from within its own organization or from competition.

9-Follow Competition: Ignoring the market place brings the inevitable downfall in an ironic turn of events. By focusing on the competition almost exclusively, the innovator eventually loses the competitive edge. New offerings invariably are introduced by competitors, eroding one’s competitive position and requiring the organization to play “catch up” with the newer innovations. The leader now becomes follower.

A good example of the dynamics of this product life cycle is the saga of “Product X” from the annals of one of America’s premier companies:

THE SAGA OF “PRODUCT X”

Year 1: A concept is tested—stimulated by intellectual curiosity, not any project objective (Vision).

Year 7: The Research Division abandons the concept. Working part time, a lone investigator in another department continues the work. When his supervisors are told of his involvement, they ask, “What are you working on that for?” The investigator stops reporting his activities.

Year 8: The product is judged to be no good. Permission is given to continue “but don’t get into any big deal about it.”

Year 9: Numerous attempts to produce a feasible prototype all end in failure (Persistence).

Year 11: The major product defect is solved. However, the new form presents a heretofore non-existent performance problem. The Vice President says to the Director, “How can your fellows fiddle around with a product we haven’t even thought of making when we’ve got more unanswered problems out here in the factories? You’re just not giving us the right kind of service! You’ve got to stop it!” The Associate Director tells the Section Head, “Don’t let it interfere with anything else he (the investigator) is doing, but do whatever he can on it. But don’t put it in your weekly report.”

Year 12: The Director decides to drop the project after extensive work by the Research Division shows no merit in the basic concept. The investigator and his managers use new test methods (quite different from the approved methods used in the past) to argue for their concept. The Director reluctantly reverses his stand and allows work to continue. Testing is hampered by manufacturing’s unwillingness to make product samples. Only one out of three requests is actually processed.

Year 13: The number of potential product options seems endless. No single formula appears to have a clear edge over the others. (Divergence)

Year 14: The Vice President is favorably impressed by the latest review of Product X. He schedules a review downtown with top management. Members of Company Management are in favor of beginning a test market. The normal two-year cycle is viewed to be a problem due to fear of competitors making a pre-emptive response. It is proposed to roll out immediately, bypassing normal blind, shipping and advertising tests. The CEO’s response is, “We’ve never done that!” (Convergence).

Year 15: The product fails to win a paired-comparison blind test before entering the test market.

Year 17: The CEO reports to the stockholders, “In our judgment, there is small chance of (Product X) replacing our existing products to any marked extent. It is a marvelous product in some fields, but limited in others, and will supplement rather than supplant our products in most homes.” The President of a major competitor, noting the modest results of the new product in test markets, claims, “This product is a flash in the pan. It won’t last!”

Can you guess what Product X is? It is something that has influenced every one of us. It is Tide, the first synthetic laundry detergent introduced to consumers by Procter & Gamble in 1948. After a modest debut, it gradually ascended to the number one market position (Market Share). The product life cycle dynamics of vision, persistence, divergence, and convergence take on a new meaning when we consider it was largely one man, supported by a few sponsors, who created this breakthrough technology against the entrenched procedures of a large and successful company!

The story of Tide’s development is not a criticism of Procter & Gamble. What this story illustrates is how powerful the forces are which shape or frustrate product/service innovation and development. Will and Ariel Durant point out the value of these conflicting forces:

“So the conservative who resists change is as valuable as the radical who proposes it—perhaps as much more valuable as roots are more vital than grafts. It is good that new ideas should be heard, for the sake of the few that can be used; but is also good that new ideas should be compelled to go through the mill of objection, opposition, and contumely; this is the trial heat which innovations must survive before being allowed to enter the human race. It is good that the old should resist the young, and that the young should prod the old; out of this tension, as out of the strife of the sexes and the classes, comes a creative tensile strength, a stimulated development, a secret and basic unity and movement of the whole.”

After its initial introduction, the momentum on Tide swung over to mass production, cost efficiencies, and similar issues. This could have seduced P&G into the cycle of Inward Focus, Win-Lose, and Follow Competition. Through the years, however, Procter & Gamble has brought out new formulas, perfumes, packaging, and even new forms (today there is a liquid Tide) in order to keep the product viable in a changing market place. Tide remains today the top-selling laundry detergent in America and its international cousin, Ariel, is the number one detergent globally. The original Tide product is out of business, but the brand name still lives on because the organization has continued to learn and adapt its product to the consumers’ changing needs. Tide is an ageless brand franchise.

And in a host of other product/service arenas, the saga of Product X has been repeated. A similar story is told at 3M regarding the adhesive for the now famous “Post it” Note. Company management first deemed the new adhesive a total failure because it wouldn’t permanently hold things together. Who would want an adhesive that would stick and then release? It took a product champion, much like the one in the laboratories at Procter & Gamble, to pursue a vision for the product now used in hundreds of ways around the world.

Think of how we got the light bulb, penicillin, overnight courier services, personal computers, and countless other items that contribute to our standard of living. In each case the product life cycle dynamics have been evident. Think further about companies, products or services that have become obsolete. Again the life cycle has been conspicuous as carriages gave way to automobiles, phonograph records have been largely replaced by compact discs, and conventional mail services have been frequently displaced by fax technology and the internet.

Again I invite you to place your own product or service where you think it fits today on the product life cycle. Are you just approaching the desired market share, already at the top, or falling from where you used to be?

In the midst of these life cycle dynamics is the potential for your organization to “jump the curve”—to renew itself before obsolescence drags you down. Your products or services may need to change through the years, but your organization can endure any season. Examine the keys to fulfilling this potential in the next article.