The recent proxy fight between Procter & Gamble and Trian Partners’ Nelson Peltz has held my attention and caused much pondering for several weeks. The Trian Partners, a hedge fund firm, believe having Mr. Peltz on the P&G board of directors would stimulate more rapid change and better returns to P&G’s shareholders. The shareholders vote on this subject is in a state of suspense as final tallies continue in the razor-thin margin. Regardless of the final, certified election results, I have been interested in what Trian said it would do if they had more say about how P&G was organized.

The Trian memorandum, “Revitalize P&G together,” is a lengthy document filled with numbers, percentages, and intercompany comparisons. Trian admitted it had only an “outside view” and needed more clarity from inside P&G, but that didn’t prevent its analysts from listing many very specific things they believed the company needed to do to improve market share, profitability, and return to shareholders.

Once again I was reminded how often we rely on numbers alone to explain the dynamics of organizational performance.

Having spent 16 years in Procter & Gamble, I want to provide some “inside” clarity on two of the organizational elements Trian proposed to “improve,” specifically:

- Restructuring the company into a holding company with three Global Business Units (GBUs)

- Scrapping the matrix structure and moving nearly all corporate functional and service associates into GBUs.

What appears so logical in Trian’s memorandum portrays problems that can be overcome without major surgery. And Trian ignores, or is ignorant of, how some of its proposals would kill many of P&G’s strengths that have taken years to develop.

Restructuring into a Holding Company

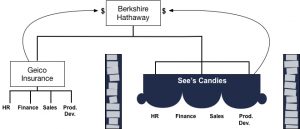

A holding company is an effective structure for a company that has several individual, non-related businesses. Each business is self-contained with its own dedicated resources.

Consider Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway company. It is a classic holding company with individual businesses in insurance, real estate, specialty chemicals, clothing manufacturers, retailers, energy, flight services, media publications, financial services, and investment companies. The only thing these businesses have in common is their owner.

This is not at all like the businesses at Procter & Gamble. All businesses are consumer products businesses: beauty care, grooming care, health care, fabric care, home care, baby care, feminine care, and family care. Not only are the management skills greatly transferrable, but also the product attributes themselves can add value to each other.

For example, P&G acquired Gillette in 2005. What both companies realized was that each “partner” could expand the other’s offerings to its core customers. Gillette dominated the men’s shaving market, while P&G had world-class expertise in skin care. Both companies had the capabilities to develop, market, and deliver new products. Gillette merged its shaving technology with P&G’s women’s skin care expertise to create the Venus razor for women. Gillette also introduced new shave lotions, deodorants, and shower gels for men using P&G’s expertise. Net, Gillette has expanded its image with customers to be the “go to” brand for men’s personal care.

Similar product synergies have emerged in the past, leading to new products and entry into new product divisions: (1) the hydrogenation process of organic substances first used to produce P&G’s Ivory soap gave birth to the concept of a hydrogenated cottonseed oil food product – Crisco shortening, (2) Absorbent tissue technology from Charmin led to the development of Pampers – the first disposable baby diaper, and (3) laundry detergent technology was applied to washing hair – and propelled P&G into the shampoo (and personal care category) business.

Organizing related businesses into a holding company would redirect management’s attention from the whole company to only their piece of the pie. Functions within that business, like research, marketing, finance, and others, would have to swim against the stream if they attempted to collaborate with other “silos.” This is not an issue where the lines of business are totally unrelated. But, as in the case with P&G, many potential synergies would not occur. Instituting a holding company structure into that business would move things back to yesteryear.

Eliminating the Complex Matrix to Increase Speed and Accountability

The matrix organization structure is, admittedly, not for everyone. Whenever the topic of a matrix surfaces in work with my clients, it unleashes a volley of frustrations and war stories. I have advised some of these clients not to construct a matrix or to get out of it as soon as possible. The problem isn’t so much with the structure itself, but with the people’s ability to shelve their desire for simple hierarchical control in a very complex marketplace.

I was in the middle of a matrix for my entire P&G career. I had two bosses in every one of my assignments as a production line manager and as an Organization Effectiveness manager in many settings. While I can understand the frustrations of others (and I admit I lived through some of the “war stories” described by others), at P&G we found a way to move forward with the right decisions most of the time. The matrix does offer the possibility of assembling all data, skills, and perspectives into one forum to (1) strategize a way to compete and win and (2) align everyone in the implementation of that strategy. The strong suit of a matrix is that it can actually accelerate the correct, aligned actions to win in the marketplace. It all depends on how people function within the structure.

Here are some basics of the matrix organization that I refer to as its “code of conduct.” Get these right and the matrix can help you swiftly examine an issue from many points of view and reduce the peril of overlooking some serious factor before charging ahead. Violate the matrix “code of conduct” and you may be plagued by the need for a series of “do overs.”

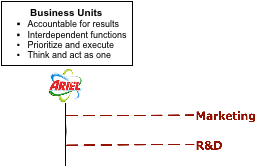

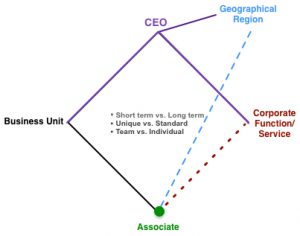

- Be clear on who makes the final call. Business Unit leaders have the final accountability (solid line in the diagram) for their business results. They may have team members from various interdependent functions and in different regions, but the GBU is responsible for the bottom line.

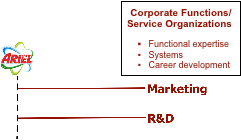

Service and Functional Organizations, on the other hand, give their support to the GBU team (dotted lines in the diagram).

Service and Functional Organizations, on the other hand, give their support to the GBU team (dotted lines in the diagram).

Good GBU leaders help their leadership teams sort through different perspectives until they all think and act as one in prioritizing and executing business initiatives at local, regional, and global markets.

Service and Functional Organizations also have some areas where they are accountable for results: to manage any functions or systems that transcend the GBUs. This may include developing expertise of those in their functions (marketing skills, innovation skills, etc.), organizing any systems that need to be common companywide (i.e., financial accounting systems, IT, hiring, etc.), and looking after the career development of their members in the GBU organizations. In the above diagram, think of these three accountabilities as their “solid” red lines.

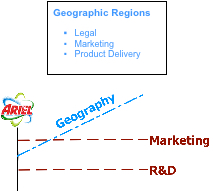

Geographic service organizations, such as legal, marketing, sales, and product delivery, are accountable to the GBU to ensure its products and services fit with the local and regional legalities and market realities.

Geographic service organizations, such as legal, marketing, sales, and product delivery, are accountable to the GBU to ensure its products and services fit with the local and regional legalities and market realities.

You can see why many view this three-dimensional matrix as overly complicated and confusing. Yet each dimension addresses significant issues that need constant attention for the good of the whole operation. Bringing all these considerations into view is the function of the GBU leader. A consideration posed by one matrix partner may be viewed as a constraint by others. But if the “constraining” consideration will make or break the market success, the team ignores it at its own peril.

Complaints about the complexity usually come from those individuals who want to have total control over their areas of responsibility. They don’t want to have to consider anything that doesn’t serve their agenda. This dynamic is what we often refer to as “silo management.” This issue is not as critical for Berkshire Hathaway as it is for a company like P&G.

Given that all organization structures are operated by imperfect human beings, one structural element, that is missing in too many matrix organizations, is the tie-breaker – someone who can make the tough call when people just can’t (or won’t) agree. This is usually the person the different matrix partners all report to. In this diagram, that tie breaker is the CEO. In other parts of the organization, it might be a general manager, a functional leader, a project leader, or similar roles.

Given that all organization structures are operated by imperfect human beings, one structural element, that is missing in too many matrix organizations, is the tie-breaker – someone who can make the tough call when people just can’t (or won’t) agree. This is usually the person the different matrix partners all report to. In this diagram, that tie breaker is the CEO. In other parts of the organization, it might be a general manager, a functional leader, a project leader, or similar roles.

- Acknowledge that there are legitimate different views on virtually any issue, such as:

- Short term vs. Long term

- Unique needs vs. Standard needs

- Team vs. Individual considerations

Each of these six considerations are legitimate and, at times, may signify the greater need or priority. A high performing organization tries to deliver both elements or at least be clear about why one takes priority over the other at the moment. If one side always wins the debates, you don’t really have a matrix regardless of what you call the diagrammed boxes and lines.

- Develop the required matrix team skills. You can see from the preceding two conduct points why the matrix is not an easy structure to implement. The following code of conduct skills can make it more effective than simpler, more mechanistic models:

- Keeping everyone’s focus on overall results, not just individual rewards, KPIs, or preferences.

- Engaging in real dialogue by listening to understand others’ points of view.

- Finding ways to shape seemingly opposing considerations into “win-win” solutions.

- Coming out with a real consensus that everyone agrees will build the business.

- Eradicating any vestiges of “command-and-control” thinking that might assume one leg of the matrix is superior to others.

In reality, one structural tool that may not be visible to outsiders is the P&G multifunctional business team. These business teams function for individual products and for business units at the local, regional, and global levels. P&G’s vaunted brand management system has been modified into category management (similar product brands organized into categories) to identify and exploit synergies. These teams may not show up on any formal organization chart, but they have driven much success. Those P&G managers who have worked on such teams have experienced how these collaborative structures have overcome most negative matrix tendencies and have increased both speed and accountability without hedge fund managers’ recipes.

Diagnose Before You Prescribe

Trian’s and Nelson Peltz’s “remedy” for P&G’s ills, based on numbers, carefully-chosen corporate comparisons, and little inside information, is analogous to you having the following conversation with your doctor:

You: “Doctor, I have painful and recurring headaches.”

Doctor: “It’s clear to me you have a brain tumor; we need to prepare for surgery.”

Question: how much confidence would you have in the doctor’s prescribed remedy (without a more profound diagnosis)?

A thorough diagnosis of the whole system is just as important for an organization as it is for your body.

Trian’s prescription in its 94-page document is a typical hedge fund formula to get immediate, short-term improvements in results. It’s obvious that Trian’s vision is limited to a five-year window. Most of the graphs comparing P&G’s performance vs. competition are for the past four to six years only. Coincidentally, research shows that hedge funds survive an average of only five years before shutting down. And their promised better results dissipate before the funds close. But the hedge fund managers always earn their sizeable management fees regardless of how well their member companies deliver.

One potential cultural issue: if the present associates in P&G have drifted away from the matrix code of conduct basics described earlier, one would expect business results to fall short of historical levels. If such drift has occurred, solving this problem, is a cultural, not a structural, issue.

A closing thought from cultural critic H. L. Mencken: “For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, – and wrong.”

Trian’s scores of numbers and carefully-chosen corporate comparisons over the recent five years aim to give one a clear and simple picture of what is wrong at Procter & Gamble.

I do believe P&G can and should do better in the days to come. But, the prescribed corrections should be made on the basis of a thorough organizational diagnosis, not a formula cooked up in a remote kitchen. Regardless of who ends up being on their board, P&G leaders need to trace the connections between culture, processes, structures, rewards, people development, and strategies in order to pinpoint what systemic issues need to be addressed and how to go about fixing them for the long haul.