This statement by Kurt Lewin, a pioneer in the fields of social psychology, group dynamics, and organization development, presents both a challenge and an opportunity for those of us working to improve our organizations’ effectiveness. “Good theory” enables us to see our circumstances as they really are. But merely seeing the reality of our circumstances isn’t enough; “good theory” should help us also see what we need to do to make lasting improvements to our circumstances.

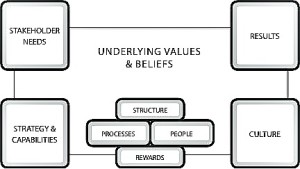

In the search for good theory, many academicians and practitioners have developed models to visualize their organizations. Everyone has their favorite model and they all consist of boxes, circles, lines, and arrows and words. Many models begin as a sketch on a napkin. They are known by various titles, such as: High Performance Models, Open Systems Models, Organization Effectiveness Models, Organizational Performance Models, or Organization Design Models.

There are few differences in what these models are intended to do. Their purpose is to create an understanding and a map from which the organization can work better. But do these different graphics, drawings, or lists actually help everyone work better?

Below are several questions that need to be asked while considering the different models that are available for your organization.

1-Is the model intuitive? Is it easy to understand, and does it make sense?

Do they require a lot of reading and do the words portray the intended meaning? Few people have the time to read a lot words these days. They skim over and focus on the most important words. Their brain fills in the missing gaps and they interpret the message. Do the models above pass the “intuitive” test?

2-Is the model easy to use? Can you follow the path of thinking easily?

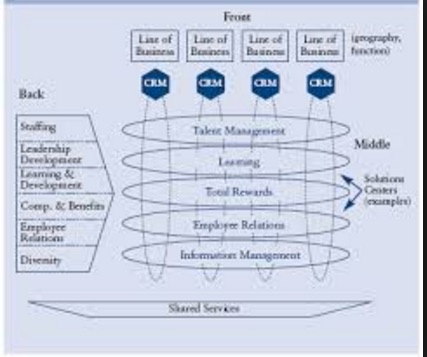

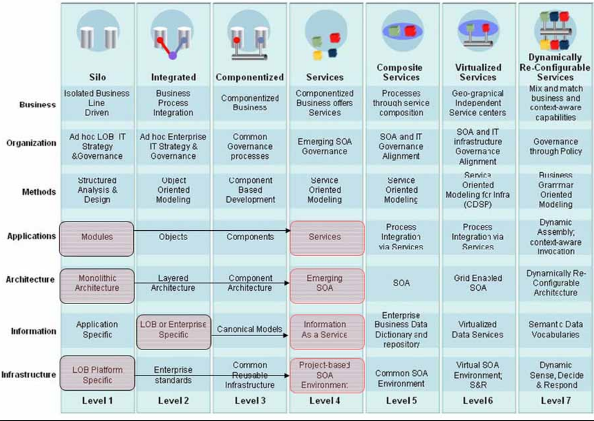

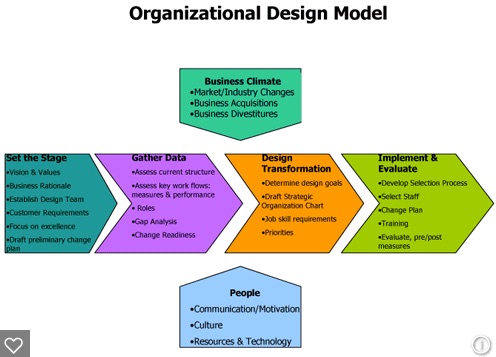

These two models are examples of popular formats. The first one is a 7 X 7 table; the second one is drawn from a 4 X 4 table. Is it clear how to use each of these models? Do you know where to start and what the next steps are? Are the different steps aligned with each other?

3- Does the model have a beginning and an end or is it a dynamic roadmap, linking back to key causes and effects in the system?

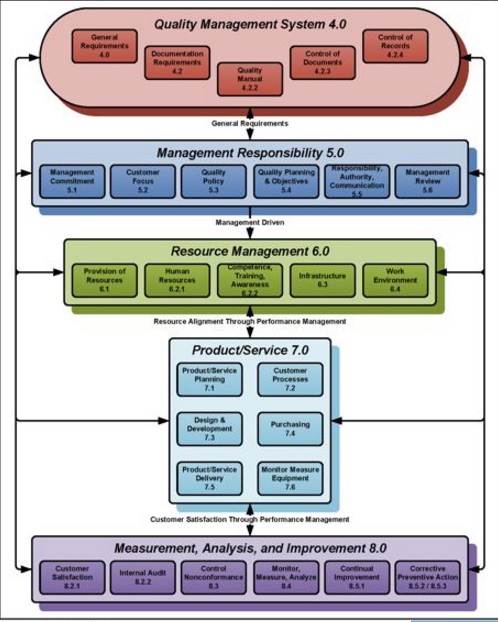

Above is an example of a linear model. This particular model contains the elements for a whole systems approach, but then it ends. An organization begins small and experiences many ups and downs in its stages of development, and then what? It ends? It stops? Hopefully, this does not accurately describe your organization’s destiny!

What do these elements look like dynamically over time? The linear model does not show the dynamic linkages to see how the different elements become both causes and effects that shape the organization’s results. And notice how the People elements are separate from the other elements. This is not how any organization actually works.

4-Can the model be applied to many different situations?

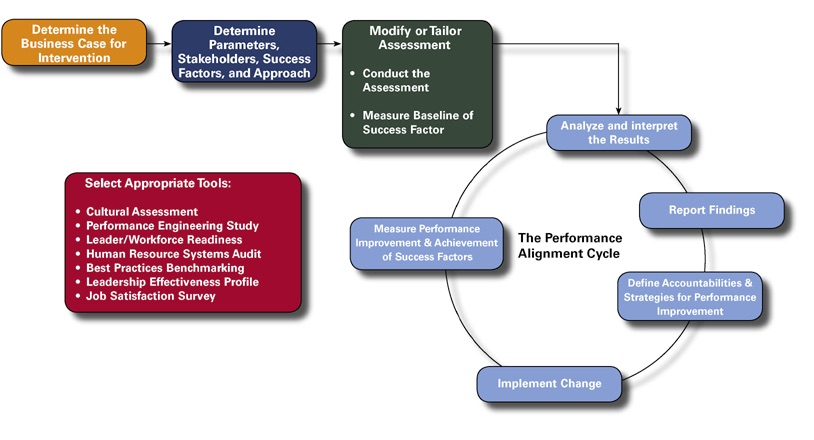

This is an example of an in-house model (or a model of a specific consulting firm’s approach) that may be helpful for its very specific purpose. But would it be helpful for other needs such as diagnosing a whole system, designing a high performance organization, changing the culture, or developing breakthrough leaders? As long as everyone understands the strengths and limitations of such a model, there is no problem. But beware of any attempt to generalize a framework for very specific needs to a broader set of issues.

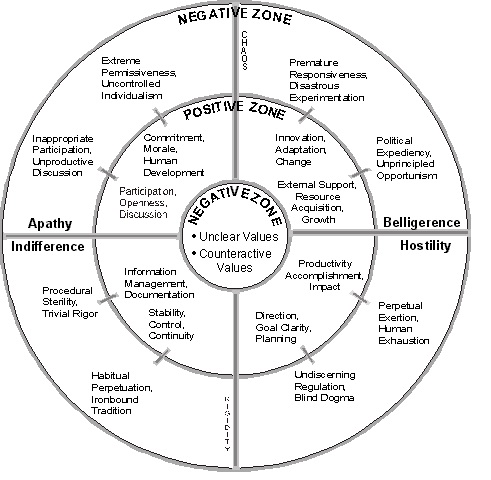

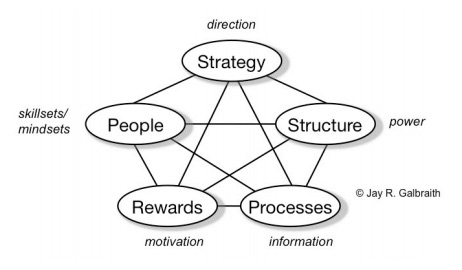

5-Does the model include both intangible and tangible organizational elements?

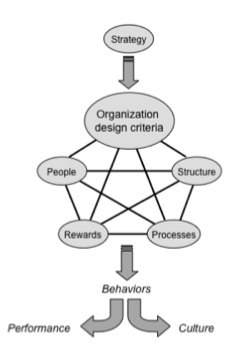

Jay later added behaviors, performance, and culture to th e Star Model, but these elements are not linked dynamically with the model’s other elements. They are depicted as mere outcomes of the organization’s design. But, in a dynamic sense, don’t they also shape many of the choices of the tangible organization design?

e Star Model, but these elements are not linked dynamically with the model’s other elements. They are depicted as mere outcomes of the organization’s design. But, in a dynamic sense, don’t they also shape many of the choices of the tangible organization design?

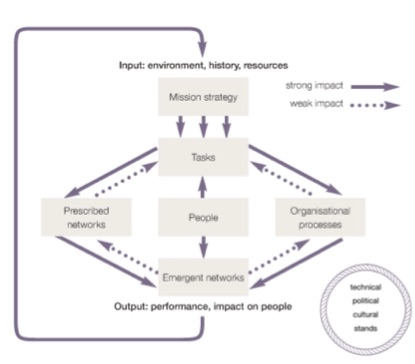

The following model is even more complete but one wonders what to do with the culture circle outside the framework. Since culture is the unseen backbone of the organization, how can it be placed outside the main framework?

Some managers say they do not like to deal with culture and they ignore it (or subordinate it) in their models. That’s like saying, “I’m not comfortable working with computers. Get them out of the picture!”

Some managers say they do not like to deal with culture and they ignore it (or subordinate it) in their models. That’s like saying, “I’m not comfortable working with computers. Get them out of the picture!”

That is not how the real world operates today.

The other difficulty with this model is the use of solid and dotted lines to imply stronger or weaker impact on other elements. This specific model may well fit the reality of one specific organization or operation, but any attempt to serve this up as a general organizational framework is highly presumptuous.

One Example of All the Model Attributes

Some years ago some Procter & Gamble internal consultants wrestled with the need to communicate clearly to business leaders how their organizations really operated according to the five criteria explored in this article:

1-Is the model intuitive?

2-Is it easy to understand/use?

3-Does it show the organizational dynamics?

4-Can it be applied to many different situations?

5-Does is incorporate the discovery of intangible data and tangible data?

Additionally, it aimed for a sixth attribute: does it give leaders a deeper understanding of why they are achieving today’s results? Here is the latest version of this model:

This is the Organizational Systems Model we use in the HPO Global Alliance to help clients understand whey their organization is “perfectly designed to get the results it gets.” The labels are not significantly different from the other models reviewed here. But notice the simplicity.

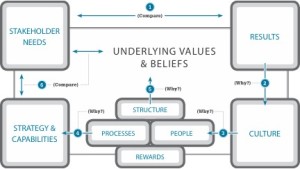

The model easily converts into a diagnostic tool illustrating organizational dynamics that are driving today’s results.

Start with Step One (comparing Stakeholder Needs with Results) and then move clockwise around the model to understand why your organization is or is not meeting Stakeholder Needs. Notice how this analysis reveals how significant tangible and intangible factors are combining to drive results.

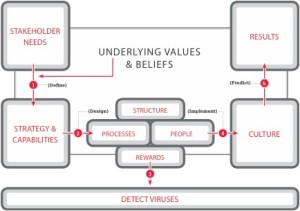

Next, the model serves as a roadmap for designing the organization to get better results.

The design process, like diagnosis, begins with Stakeholder Needs and then proceeds counterclockwise to develop full alignment with those needs. Step One is to define Strategy and Organizational Capabilities that will lead to meeting Stakeholder Needs. Underlying Values & Beliefs that were found to be short circuiting the rest of the system in diagnosis can now be altered from “This is how we think today” to “This is how we should be thinking from now on.” The “should” statements become part of the new strategy. There are hundreds of approaches, processes, and technologies that could fit into the Processes, Structure, Rewards, and People boxes, but those that are chosen should be aligned with the Strategy and Stakeholder Needs.

Practical use of this model in hundreds of organizations over the past four decades in a variety of organizations, industries, geographies, and cultures has proven it to be user friendly and profound in helping companies improve their results. It has met the six criteria for an effective model.

Not all of these companies embraced the model exactly as depicted here. Some labels were adjusted to fit with the company’s existing vernacular. The format was adjusted by some to their liking, but the process relationships remained intact.

One thing we have learned from all the users of this model: it’s true value is not in its shape or form, but in how it changes the thinking of those who use it. Once you have “downloaded” whole systems thinking into your head, you are not as dependent on one specific model.

The Organizational Systems Model does indeed represent simplicity on the far side of complexity.