How mastering the dynamics of a matrix structure can enable high-performance streaming in our Digital/Global Age

Mention the words “matrix organization” or “matrix structure” to anyone who works in one and you will never find a neutral response. Most people loathe the matrix, though some sing its praises. Why the different reactions and what is behind the strong emotions on both sides of this coin?

My purpose here is to make the matrix more transparent to both its critics and defenders and to point out how mastering the dynamics of a matrix structure can also enable high- performance streaming in today’s Digital/Global Age.

Tectonic Shifts and Organizational Responses

Throughout history tectonic shifts have moved marketplaces in drastic ways, leaving some organizations with advantages and leaving others out of business. Some notable tectonic shifts include:

- The shift from the Agrarian Age to the Machine Age.

- The shift from the Machine Age to the Digital Age.

- The shift from Local Markets to Global Markets

Each of these tectonic shifts has required organizations to reinvent how they operate in order to be competitive. Let’s consider two of these shifts: (1) from Agrarian to Machine Age and (2) from Machine Age to Digital Age.

Bureaucracy: a new form of organization for the Machine Age

Bureaucracy is not a term criticizing organizations; it is a set of organizing rules articulated years ago by theorists such as Frederick W. Taylor and Max Weber. Bureaucracy’s rules attempt to organize work in a mirror image of the system of machines that launched the age of mass production. Indeed, bureaucracy assumes an organization is like a machine; a collection of parts driven by a single control mechanism. Flowing from this assumption are six basic rules:

- Task Specialization—“job fragmentation”… tasks are specialized and reduced to the smallest possible work cycle. Like single cogs in a wheel, workers perform simple tasks that collectively yield a complex output.

- Performance Standardization—“find the one best way”… work is to be performed the same way every time. No exceptions! The technical monument to this thinking is the assembly line. But even administrative processes can be organized in a sequential flow like an assembly line.

- Central Decision Making—“unity of command…” decision making is exclusive to those in authority. The boss makes the decisions much like the machine controls all of its parts.

- Uniform policies—“that’s what the book says”…. all parts of the system are treated alike. Like a well-oiled machine, people operate according to policy, often making no provision for specific customers’ or associates’ needs.

- No duplication of functions—“that’s not my job!”…. tasks are handled exclusively by those assigned. Otherwise, many hands might disturb the efficiency and consistency of the task.

- Reward physical activity—“the hired hand”…. a person is paid for

physical labor and skills. Hourly pay rates, piece-rate incentives, and even bonuses focus the individuals’ work efforts on their expected output. Innovation, customer service, and process improvements are often someone else’s responsibility.

physical labor and skills. Hourly pay rates, piece-rate incentives, and even bonuses focus the individuals’ work efforts on their expected output. Innovation, customer service, and process improvements are often someone else’s responsibility.

How have these six rules affected our society? Without question they have outperformed the agrarian society from whence they sprang. They have enabled us to mass produce goods, thereby contributing to a higher standard of living for everyone. They do delineate job responsibilities across departments and up and down the hierarchy. And they drive out ambiguity.

But the rapidly changing needs of customers, suppliers, and associates have made bureaucracy somewhat out of balance for the Digital/Global Age. The very root of bureaucracy’s problems lies in the core assumption itself: an organization is like a machine. Customers, suppliers, and associates are not machines. In ages past these stakeholders have complied with the organizational work rules. But individuals today are resisting them more and more. And these rules are failing to meet the global markets’ needs as well as they met the early industrial markets’ needs. Despite its shortcomings, bureaucracy is still the most common organizational form on this planet.

One example of an inefficient, but “in control” bureaucracy was the automobile license registration bureau in a city in which we once resided. The registration process was clearly laid out:

- Fill out the registration forms

- Pay the license fee

- Turn in your old plates

- Pick up the license plates (each one machine stamped while you wait)

- Obtain the official stamp on the paperwork, signifying that everything is in order

Each step was in a separate location (in two different buildings) and was identified by the long line of people waiting to be served. I had to wait in line for one hour for my license plates while the operator of the stamping machine went to lunch. Not knowing that I had to turn in my old plates before getting the new ones, I had to get out of line, drive home and retrieve the old plates off the family vehicles before re-entering (at the back of) the line.

The entire process consumed the entire day. It adhered to all of the rules of bureaucracy, but was nerve wracking to its customers.

I have shared this experience with people in different countries in all corners of the world and the universal reaction is “That sounds just like our license bureau!”

Matrix: a new form of organization for the Digital/global Age

Matrix structures were invented in the aerospace industry because the typical bureaucracy “silos” were unable to respond/ adjust fast enough to rapidly changing technologies and their impact on market dynamics. This challenging environment has only accelerated in the Digital/Global Age.

The matrix offers the possibility of assembling all data, skills, and perspectives into one forum to (1) strategize a way to compete and win and (2) align everyone in the implementation of that strategy. The strong suit of a matrix is that it can actually accelerate the correct, aligned actions to win in the marketplace. It all depends on how people function within the structure.

But the matrix is, admittedly, not for everyone. Whenever the topic of a matrix surfaces in work with my clients, it unleashes a volley of frustrations and war stories. I have advised some of these clients not to construct a matrix or to get out of it as soon as possible. The problem isn’t so much with the structure itself, but with the people’s ability to shelve their desire for simple hierarchical control in a very complex marketplace.

I was in the middle of a matrix for my entire Procter & Gamble career. I had two bosses in every one of my assignments as a production line manager and as an Organization Effectiveness manager in many settings. While I can understand the frustrations of others (and I admit I lived through some of the “war stories” described by others), at P&G we found a way to move forward with the right decisions most of the time.

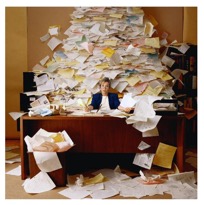

“A senior manager in another company once told me, “Since we have initiated the matrix organization, things have almost come to a standstill. Everyone feels they need to be informed of everything and they expect to give their consent before anything can move forward. Every level of hierarchy, every location, every function–they all must sign on or it’s no deal. No two players see things the same way. We have become a debating society.”

Of the many managers I have met who criticize the matrix, I have found very few who actually understand the principles behind it.

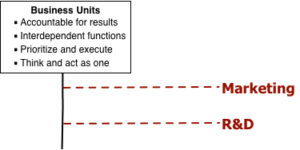

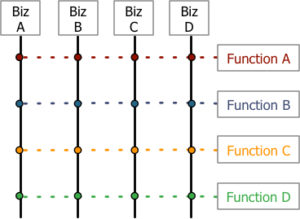

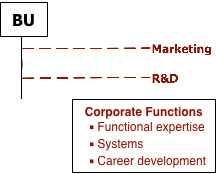

As this graphic illustrates, the matrix maps out relationships between Business Units (Biz) and Corporate Functions. Solid lines mean direct accountability; dotted lines symbolize support or advisory responsibilities.

Those accustomed to bureaucracy’s clean lines of authority become uncomfortable with the idea of two lines converging on one person or unit. The question of who has the solid line and who has the dotted line becomes a hotly debated topic in many corporations.

Those accustomed to bureaucracy’s clean lines of authority become uncomfortable with the idea of two lines converging on one person or unit. The question of who has the solid line and who has the dotted line becomes a hotly debated topic in many corporations.

Some “experts” advise doing away with dotted lines and giving everyone a solid line. This is a simplistic, cosmetic solution to a much deeper problem. If individuals want to shed their dotted line, it is probably because they want the final say or at least the right to veto. Either one defeats the purpose of collaboration and dialogue. In reality, not everyone has a veto or final decision-making right. So why pretend that they do?

Generally, the debate should be settled by answering this question: with which unit do you want the associate to identify? If it is important that he/she identify fully with the BU team, then that should be the solid line. If, on the other hand, an associate must give priority to his/her professional responsibility (even if contrary to the BU’s wishes), then the solid line might be better with the function.

Frequent complaints about the matrix include:

- Responsibilities are unclear

- Decision making authority is a source of contention

- Associates are confused about whose directives they should follow

Such complaints have two possible root causes: (1) the roles indeed have not been clearly defined or (2) those who want to hold on to their control and decision rights deliberately frustrate efforts to clarify things, thus maintaining the status quo.

Let’s address each of these root causes, beginning with the matrix structure’s design principles. What are the intended roles for the different players?

- The Business Units (BUs)are typically the profit centers and accountable for the business results. Functional resources are assigned to the BU to apply their expertise to the business needs. The intent is for the Business Unit team to have all the needed resources, yielding better and faster execution. (In other words, being self-sufficient to fulfill its accountability.) Good BU leaders help their leadership teams sort through different perspectives until they all agree and can think and act as one in prioritizing and executing business initiatives at local, regional, and global markets.

- The Corporate Functions play a very different, but critical role in the matrix. They provide the team members who must collaborate to make the BU successful. These are the dotted-line players. However, there are a number of issues related to the functional resources, such as:

- How does the organization ensure that the functional resources in the BUs have the right expertise?

- How does it avoid creating unnecessary complexity by doing common tasks very differently in each BU?

- Who looks after the career interests of functional professionals assigned to a BU today?

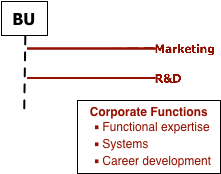

These are all issues that transcend an individual BU; therefore, the Functions should manage them. The Functions are the developers of each person’s technical expertise, the designers and keepers of the common functional systems, and the mentors and orchestrators of the professionals’ careers who are in their functional discipline. Addressing all of these issues should be done in collaboration with the BUs. In this diagram, think of these three accountabilities as the Functions’ “solid” red lines.

These are all issues that transcend an individual BU; therefore, the Functions should manage them. The Functions are the developers of each person’s technical expertise, the designers and keepers of the common functional systems, and the mentors and orchestrators of the professionals’ careers who are in their functional discipline. Addressing all of these issues should be done in collaboration with the BUs. In this diagram, think of these three accountabilities as the Functions’ “solid” red lines.

Again, those who are used to bureaucracy’s “unity of command” get nervous when someone suggests BUs have the final call on some issues and Functions have the final call on others.

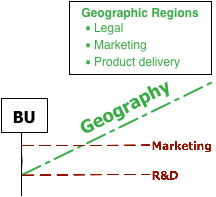

- The Geographical Region. The emergence of global markets has driven this additional dimension of the structure for many companies. Somewhere in the blend of BUs and Corporate Functions is the additional need to tailor the

operation to unique needs of a Geographical Region of the world. Despite the many commonalities of today’s global market, there are still cultural differences, legal differences and large distances to be managed. The principal regional role is to manage product delivery, marketing executions and legal requirements that are unique to the local area. Obviously, the Regional organization must partner with the BUs and the Functions to make everything come together.

operation to unique needs of a Geographical Region of the world. Despite the many commonalities of today’s global market, there are still cultural differences, legal differences and large distances to be managed. The principal regional role is to manage product delivery, marketing executions and legal requirements that are unique to the local area. Obviously, the Regional organization must partner with the BUs and the Functions to make everything come together.

A MISSING PIECE

There is one piece of the matrix structure that I have not yet addressed. It is also an element that many corporations do not address.

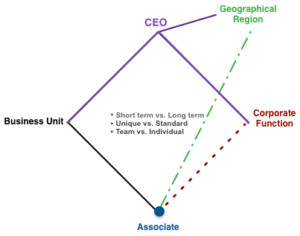

Given that all organization structures are operated by imperfect human beings, one structural element, that is missing in too many matrix organizations, is the tie-breaker – someone who can make the tough call when people just can’t (or won’t) agree. This is usually the person the different matrix partners all report to. In this diagram, that tie breaker is the CEO. In other parts of the organization, it might be a general manager, a functional leader, a project leader, or similar role. If the three legs of the matrix cannot come to agreement on how to proceed with cost cutting, or associate career development, or marketing campaigns, someone must be able to resolve the issue. In those cases the role of decision maker falls to the CEO.

Given that all organization structures are operated by imperfect human beings, one structural element, that is missing in too many matrix organizations, is the tie-breaker – someone who can make the tough call when people just can’t (or won’t) agree. This is usually the person the different matrix partners all report to. In this diagram, that tie breaker is the CEO. In other parts of the organization, it might be a general manager, a functional leader, a project leader, or similar role. If the three legs of the matrix cannot come to agreement on how to proceed with cost cutting, or associate career development, or marketing campaigns, someone must be able to resolve the issue. In those cases the role of decision maker falls to the CEO.

You can see why many view this three-dimensional matrix as overly complicated and confusing. Yet each dimension addresses significant issues that need constant attention for the good of the whole operation. Bringing all these considerations into view is the function of the BU leader. A consideration posed by one matrix partner may be viewed as a constraint by others. But if the “constraining” consideration will make or break the market success, the team ignores it at its own peril.

Now let’s dig deeper to understand those who want to hold on to the status quo and who then deliberately frustrate efforts to clarify roles and responsibilities in the matrix.

Matrix Cultural Attributes

The Machine Age brought automation to a world of hand labor. The matrix brings team synergy and performance streaming to a world of bureaucratic silos. Both tectonic shifts have not come without some pain and strain for those who do the work.

A matrix structure requires digital-like streaming by all members of the system. Partnering, teaming, collaborating, and networking are the cultural attributes of a successful matrix organization. The three legs of the matrix are interdependent in the operation of the business. The structure is designed to keep everyone’s attention on the overall results—to stimulate dialogue, examination of business issues from multiple viewpoints, and synergistic problem solving.

A matrix structure requires digital-like streaming by all members of the system. Partnering, teaming, collaborating, and networking are the cultural attributes of a successful matrix organization. The three legs of the matrix are interdependent in the operation of the business. The structure is designed to keep everyone’s attention on the overall results—to stimulate dialogue, examination of business issues from multiple viewpoints, and synergistic problem solving.

One barrier to these cultural attributes is “either-or” thinking. We must think EITHER long term OR short term.

Effective organizations have the capability to examine the needs of both long-term AND short-term. The players in a matrix have the potential to dump “EITHER-OR” thinking and shape such a culture of AND.

If, on the other hand, one side always wins any of these either-or debates, you don’t really have a matrix despite what you might call the boxes and lines. Also, if this true AND teamwork exists in the company culture, it makes little difference who has the solid line and who has the dotted line.

A senior R&D manager once explained to me how he and his team had helped make Ariel laundry detergent the top global brand.

“Our research indicated we had three major laundry washing conditions: (1) Hot temperatures (up to and including the boil wash), (2) Cold temperatures, and (3) hand washing in some countries. I told my team, ‘Let’s develop a detergent that cleans clothes equally well in all three conditions.’

‘That can’t be done,’ they told me.

‘I won’t approve going forward until you find a way to do it.’

They worked hard on it and finally developed a formula that was superior in all three conditions. Because these three conditions also define the global market, it’s easy to see why Ariel became number one globally.”

Solving three needs simultaneously with one product is a tangible example of what I call performance streaming.

The following examples are indicative of a culture that has not yet reached performance streaming:

- BUs’ and/or Geographical Regions’ first reflex is to refuse to adopt a Corporate Functional system because “our needs are different.”

- Corporate Functions unilaterally impose a corporate policy or system and clash with the BUs in the process.

- BUs refuse to consider transferring a person because of “the needs of the business” even though that person needs (and deserves) a broader assignment.

- Corporate Functions attempt to downsize or cut costs in order to “improve their numbers” to the CEO—without consulting the BUs.

You get the picture–well-meaning people being distracted by personal priorities in isolation from the bigger picture. Without true partnership relationships, the matrix can be a complex and frustrating structure in which to work. Managers, who are used to the crisp, precise responsibilities in a bureaucracy and who thrive in a “command and control” system, will be frustrated in a matrix. They don’t want to have to consider anything that doesn’t serve their agenda. They want to be able to exercise simple hierarchical control for their small piece of a very complex marketplace. This dynamic is what we often refer to as “silo management.”

Despite the many challenges and opportunities in today’s marketplace, I am amazed at how many people still cling to the structural support and behavioral habits of bureaucracy.

So, if you truly do want to shape a matrix culture, how do you go about it? Where do you begin? What follows are some practices that I have seen that make a difference.

The Rules of Engagement

Military rules of engagement spell out how to think and respond in combat and in times of stress. Here are the rules of engagement for stressful times in the matrix:

- Always remember: the aim is to improve overall results, not necessarily every department’s targets or every individual’s KPIs.

- The focus on overall results requires:

- Collaboration

- Dialogue

- Consensus (e.g., all can at least support the decision and move forward)

to understand all dimensions of the issues, identify the right strategies, and mobilize all players in seamless implementation of those strategies.

- Flexibility is key: this translates into being willing to “rethink” your position on an issue and always looking for innovative ways to meet constantly changing market and customer needs.

When these statements reflect how the organization really operates, its teamwork will outperform bureaucratic competitors. Here is an example of the geographic perspective adding value to the business units and functions:

One client was trying to improve profitability in Europe by getting nine countries to make practical decisions on product formulas and packaging for its consumer products. Though market research showed consumer preferences were converging in many areas in the nine countries, each country still did its own research and distributed its own unique product and package. The pride of invention was very strong in all nine countries.

Multifunctional teams were organized for each major brand to test the feasibility of one version of its product and package in all nine countries. Each team not only had all functions represented, but also had representatives from large and small markets as well. This was no cookie cutter system. Market data for many products indicated a single offering in a multi-lingual package was feasible. Only a few products had more than one product formula and package because that’s what the market data indicated was needed.

The results of this team system were staggering. Profits across Europe tripled in 18 months. One manager from one of the smaller countries explained how the business units, functions, and geographic interests all came together in true synergy:

“With our staff and financial resources, we could only bring out three or four new or improved products in a year. This past year we launched 13 new/improved products. We had representatives on several teams, so we knew the product plan had our input and met our needs. And they all delivered for us!”

The Code of Conduct

Here are some basics of the matrix organization that I refer to as its “code of conduct.” Get these right and the matrix can help you swiftly examine an issue from many points of view and reduce the peril of overlooking some serious factor before charging ahead. Violate the matrix “code of conduct” and you may be plagued by the need for a series of “do overs.”

- Be clear on who makes the final call on specific decisions. Business Unit leaders have the final accountability (solid line in the diagram) for their business results. They may have team members from various interdependent functions and in different regions, but the BU is responsible for the bottom line. As mentioned previously, the Functions make the final call on systems that transcend individual BUs.

- Acknowledge that there are legitimate different views on virtually any issue, such as:

- Short term vs. Long term

- Unique needs vs. Standard needs

- Team vs. Individual considerations

Each of these six considerations is legitimate and, at times, may signify the greater need or priority. A high performing organization tries to deliver both elements or at least be clear about why one takes priority over the other at the moment.

- Develop the required matrix team skills. You can see from the preceding two conduct points why the matrix is not an easy structure to implement. The following code of conduct skills can make it more effective than simpler, more mechanistic models:

* Thinking synergistically: Aristotle said, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” This is the principle of synergy, as these two sketches illustrate:

These parts are of little value unless they combine into a purposeful whole. Optimizing the whole usually means some parts are sub-optimized.

but is each part is optimized, then it is likely the whole will be sub-optimized.

* Engaging in real dialogue by listening to understand others’ points of view.

* Finding ways to shape seemingly opposing considerations into “win-win” solutions.

* Coming out with a real consensus that everyone can support to build the business.

* Eradicating any vestiges of “command-and-control” thinking that might assume one leg of the matrix is  superior to others.

superior to others.

These skills are important for any team.

STREAMING: A KEY to HIGH Performance in the Digital/global Age

Now, let’s set aside the matrix structure and consider the Digital/Global Age in which our organizations operate:

- The rate of innovation in all dimensions of life has increased dramatically.

- Product lifecycles and shelf lives are shrinking.

- New products and services are exploding upon the scene.

- Stakeholders’ expectations are in a constant state of flux

- Yesterday’s leaders are becoming today’s followers.

These dynamics are not unlike the impact of the Machine Age on the Agrarian Age–only they are perhaps even more dramatic and they are “in our face” now.

Against this scenario of Better–Faster–Shorter, hold up how your organization really operates with actions, improvements, and decisions traveling up and down multiple silos in sequential paths, then competing for resources laterally with other business units and functions, and finally traveling up several layers of hierarchy before getting the final approval (a grander version of the automobile license bureau?). It often feels like trying to run a 100 meter dash in a lane full of thick mud. Small wonder that approximately half of the world’s top 100 corporations fall off that list every 10 years.

The machine model alone can’t compete against digitalization. Nor can neighborhood convenience any longer outperform Digital/Global reach.

Organizational technology like the Rules of Engagement and the Code of Conduct can bridge the gap. Partnering, teaming, collaborating, and networking can facilitate organizational streaming much like sophisticated digital technology streams global data to your computer screen or completes complex data analyses in a matter of seconds. As you will see, this is not merely a conceptual metaphor.

Think about typical situations in your work place. How many issues in your work require a group to come together to:

- Create a new opportunity?

- Solve a perplexing dilemma?

- Understand the “big picture”?

- Get everyone on the same page?

To accomplish any of the things listed above, wouldn’t it be ideal if you could assemble a team of diverse talents and experiences, pick each other’s brains, and agree on how to best move forward?

Your challenge might involve a few people or many; it might be in one location or in different corners of the world. And your group might have such organizational titles as:

- A multifunctional team

- A research group

- A project team

- A board of directors

- An executive committee

- A network

- An innovation group

Now look back at the Rules of Engagement and the Code of Conduct. Aren’t these guidelines just as relevant to your challenging situation and to your group that needs to deliver better results? Wouldn’t their capacity for streaming outperform your historical approaches?

the battle between your bureaucratic traditions and leadership habits versus the requirements of today’s Digital/Glo0bl business environment. A prime example of organizational streaming in a battle for survival comes from Silicon Valley and the work of my good friend and consultant Ord Elliott.

Ord’s client, “StorServ”, a network storage company, learned that a competitor was going to deliver a superior product in six months that was sure to drive StorServ out of business. Though StorServ had its own improved product in the works, there was little hope for beating the competitor to market. StorServ’s typical product development rollout history was thirteen months from concept to product.

Senior managers set a target to deliver their new product in five months, but they had no specific plan on how to accomplish this. This functionally fragmented operation would require extensive dialogue and tradeoffs across functional boundaries to meet its target. To make matters worse, a pre-assessment showed virtually no employees in the heart of these functions had any of the needed leadership experience.

Some experienced associates identified 25 different functional areas whose collaboration would make or break

success. They formed multifunctional teams in each of the 25 areas made up of hardware and software engineers and representatives from marketing, operations, and finance. Each of the 25 teams was responsible for one of the features of the new product and would have to collaborate with several other teams simultaneously to deliver their feature. (And you think your matrix is complex!)

With few experienced leaders, each team discussed how to move forward. Each team had three or four members who felt they could lead some of the required areas. So, their leadership structure looked like this:

Each team’s chosen “connectors” (red figures in this diagram) had the responsibility to connect with other teams that were working on items that were also critical to their team’s feature. Because these connections didn’t have to flow through one team leader, overlaps and differences were addressed simultaneously and practical compromises swiftly were agreed to in the interests of the larger objective.

Senior management demonstrated remarkable restraint by not interfering with this process or requiring lengthy review meetings to make them comfortable with what the team experts were accomplishing.

The bottom line of this new organizational system? One true miracle. StorServ beat its original five-month delivery target; it delivered the new product in a mere three-and-a-half months–and it did indeed outperform all competitors. The company was saved and several thousand associates’ jobs also were saved.

Vive la Streaming!

As this case study illustrates, the guidelines discussed in this paper are essential cultural attributes for succeeding in our Digital/Global Age.

Harvard Emeritus Professor Chris Bartlett says, “Structure is a blunt instrument for regulating organizational behavior.” Indeed, it is the organizational culture (i.e., Rules of Engagement and Code of Conduct) that bring any structure to life.

Going through the pain of reshaping your corporate culture will not always be pleasant, but it will bring priceless rewards in the end. Just ask the thousands of associates at StorServ.

As W. Edwards Deming used to say, “Improvement is not compulsory; it’s voluntary. It’s only a matter of survival.”